George Argyle and the beginnings of the Argyle Dairy

The Argyle family have lived in the Abingdon area for a long time. In 1775 Richard Argyle of nearby Sutton Wick married Ann Barnett in Abingdon, where she had been born. Their son Richard was grandfather to George Henry Argyle (1865-1945), my great-grandfather and founder of the Argyle Dairy.

George Argyle’s family were nonconformists. Two of his uncles became Baptist pastors – they were teetotallers as their nephew George would be. A niece, Olive, was one of the first two women to be made deacons of Abingdon Baptist chapel. Percival, a nephew, was a local journalist and reported on the First World War.

The Argyle name has been well known in Abingdon for another reason: the tradition of morris dancing and the mock mayor of Ock Street. George’s younger brother Albert was grandfather to the late Leslie Argyle who was prominent in morris dancing in both Abingdon and in Oxford for many years. He led the Abingdon Traditional Morris Dancers and was elected as ’mayor’ of Ock Street every year from 1980 to 1995.

In 1881, according to the census that year, George Henry Argyle was a sixteen-year old dairy boy living with his parents in Edward Street in Abingdon. The milk industry was good for George in more ways than one. Delivery of dairy products may even have led to his marriage. His future wife probably met him regularly twice a day in the course of their work because part of his delivery route lay along Marcham Road where Ellen Sessions lived and worked with her sister Eliza in the home of Bromley Challenor, Town Clerk of Abingdon. The young women had left their parents in nearby Wantage to earn livings as domestic servants. In 1889 George and Ellen were married.

In the 1891 census year, George Argyle was a dairyman living in Ock Street with his wife Ellen and infant son Arthur. Ten years on, the 1901 census records him as a milk purveyor living with his wife and now three children at 14 Victoria Road. Part of that building, located on the corner of Edward Street and Victoria Road, served as his newly owned dairy. This happy change in status had been made possible unexpectedly by the dishonesty of George’s former boss. A little detective work had told George that his employer was watering down the milk which he, George, must sell to disgruntled customers. When he worked out what was going on he left, and in a daring move took the risk of starting up his own business. The Argyle Dairy quickly did well enough to have its name inscribed over the main door.

The Argyle Dairy in about 1904, after the sale of the dairy to Charles Burt (standing at the entrance) who continued to use the Argyle Dairy name

(© From the author’s private collection)

The former Argyle Dairy, now a private house, in 2013

(© From the author’s private collection)

George and Ellen had four children, John, Nellie, Gertie and Arthur, Gertrude Florence Mary being my grandmother. The family lived behind and over the dairy and were successful enough to employ a maid who wore the typical black dress, white apron and cap of servants in well-to-do Victorian and Edwardian homes.

John, Ellen, George, Nellie, Gertie, Arthur

(© From the author’s private collection)

The couple followed a steady routine. Each morning George got fresh milk from a farmer along Spring Road and returned home standing on his horse-pulled cart, a large urn full of milk lodged beside him for company.

A milk cart similar to the one George Argyle would have used.The photograph was taken in about 1920 in Edward Street just round the corner from the front of the dairy building in Victoria Road. It is in the possession of Barbara Ayers, great-granddaughter of Charles Burt who bought the dairy from George Argyle.

(Copyright By kind permission of Barbara Ayers)

It was then the job of Ellen, my great grandmother – his full working partner – to filter the milk through clean cloths and pour it into tin containers which were measured in gills and pints. Pasteurization was not yet part of their dairy’s process. The rest of the milk was poured into a fresh and clean urn which would be hoisted up onto the cart. George would dispense whatever quantity of milk a customer might need into his or her own jug right at the householder’s door, or the customer could buy a standard amount.

In the afternoon the pattern was repeated. George’s two older children helped a bit. Arthur earned six pennies weekly for his deliveries by pushcart to houses beyond his father’s own route, and Gertie earned three pennies for light loads carried to two homes in Spring Road. Meanwhile on the Argyle Dairy premises Ellen washed all surfaces thoroughly, churned butter, made cream and served as a salesperson.

But George had another interest which would overwhelm all else in his life. In the years of his marriage and parenthood, if not earlier, he was known to be an avid reader of Biblical scripture. Around 1900 a sect known as Russellites was becoming popular. They would later rename themselves Jehovah’s Witnesses. George became one of them and in 1903 he sold the Dairy outright, much against Ellen’s advice.

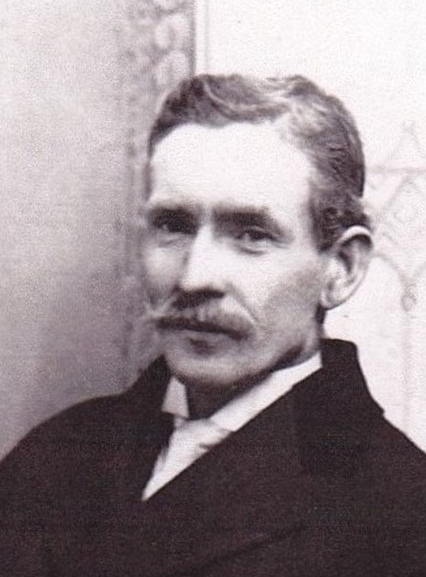

George Henry Argyle holds a religious text entitled The Finished Mystery. This work, the seventh in the series Studies in the Scriptures by Charles Taze Russell, was published posthumously in 1917.

(© From the author’s private collection)

George’s sale of the dairy marked the end of the Argyles’ hard-won prosperity. He took the family from Abingdon, the long-time home of the Argyles, to Reading where he could much more readily attend Russellite meetings. The Battle Street general store which they purchased in Reading turned out to be a very short-term experience. Ellen suffered violent headaches from the fumes of kerosene which was sold from barrels at the front of the premises. Then it was on to an attempt at market gardening in Tilehurst which yielded meagre profits.

Their eldest son, Arthur, had gone to Canada in 1911. He claimed that ample employment was available in Toronto and urged his father to emigrate. George took the challenge and uprooted the family once again. George, Ellen, Gertie, Nellie, John, and Gertie’s new husband Jack Ledsham all voyaged across the Atlantic Ocean in April 1913 aboard the steamship Ascania en route to Portland, Maine and then to Toronto.

When George moved his family to Reading he sold the dairy to Charles Burt who continued to use the Argyle Dairy name.

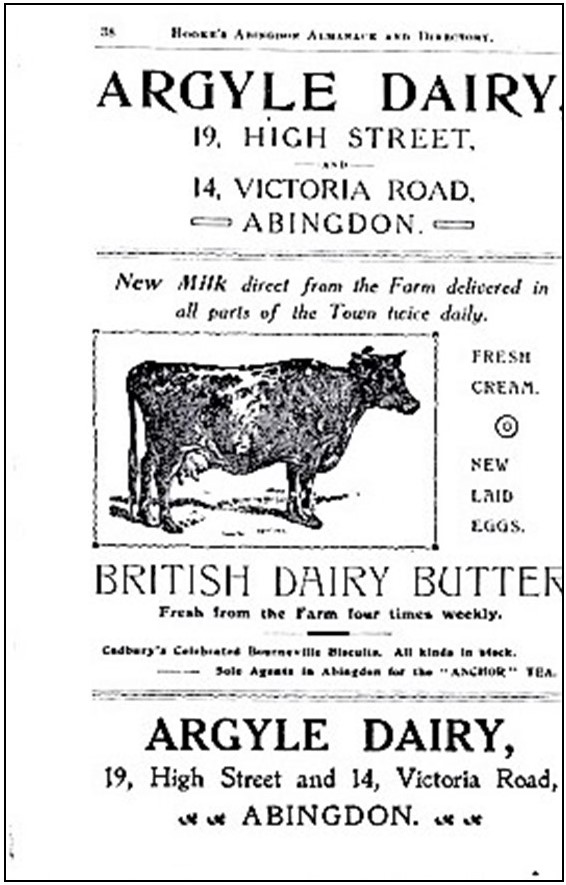

Full page advertisement in Hooke’s Abingdon Directory 1916.

(© With thanks to Oxfordshire libraries)

Some thirty five years later, the Burt family sold the business on. It was eventually acquired by James Candy, the main local competitor, who adopted the Argyle name – the combined business was called the Argyle & Candy Dairy. It was only when United Dairies, a much larger concern, took over the business in the 1990s that the name Argyle ceased to be connected with the milk trade in Abingdon.

George Argyle died in Toronto in 1945 and Ellen in 1957.

George and Ellen’s grave marker in Toronto. Some of their descendants had Ellen’s dates added to the marker early in 2020.

(© From the author’s private collection)

Sandra Marie Lewis

© AAAHS and contributors 2020