The former Lion Hotel, High Street (partly demolished)

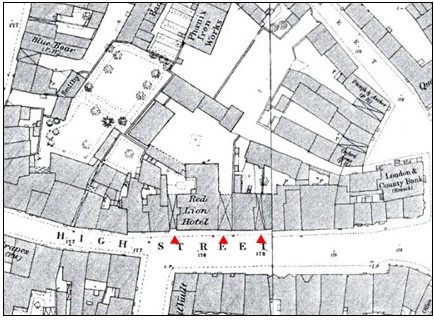

Figure 1. Lion Hotel, Abingdon

Postcard from a private collection, ca.1900. Scan kindly provided by the owner. Origin unknown. We have been unable to trace a copyright holder.

When it closed in 1936 the Lion Hotel consisted of two previously separate establishments, the Lion (sometimes called the Red Lion) which was a five-gabled building to the left of and above the carriageway (Fig. 1) and the King’s Head (not to be confused with the King’s Head and Bell in East St Helen Street) which was in the twin-gabled building to the right of the lamp-post. This in part survives today and still provides hospitality as a coffee shop and restaurant above at No.15 High Street.

Figure 2. The site of the former Lion (on the left) and King’s Head (with two gables) in 2010

(© D Clark)

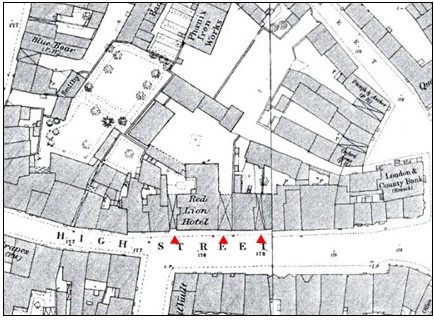

The entire range of five gables has now gone, and early maps and photographs are the only evidence we now have for the building. Although it had jetties at two levels and oriel windows to the first and second floors, the size and uniformity of the building suggests that this is a façade deliberately obscuring the two separate structures behind that can be identified on nineteenth-century maps. The first edition of the Ordnance Survey map (Fig.3) shows that there were three passageways from High Street into the area behind. The westernmost went into the enclosed yard of the Lion, the central into an open yard with the cattle market behind, and the eastern into another (almost closed) yard behind the former King’s Head.

Figure 3. High Street Abingdon with the Red Lion in 1874 from the 1st ed. OS map. The passages into the yards behind the hotel are marked by red triangles.

By permission of www.old-maps.co.uk

© Crown Copyright and Landmark Information Group Limited 2020 all rights reserved.

The tall gabled structure over the central carriageway into the rear courtyard (see Fig. 1) was almost certainly relatively modern. The adjacent part of the King’s Head – which dates from 1291 – was jettied both to the High Street and to a passageway to the west. This was probably built over to form the hotel entrance when the two pubs were united in the mid-nineteenth century. Before this, the main entrance to the Lion appears to have been on the High Street, in the rather wider gap between the central ground floor windows shown in Figure 1.

There is no firm documentary evidence for the Lion before 1787, though a Red Lion was mentioned in 1734 and there is a tradition that when John Wesley visited Abingdon on 2 July 1741 he preached in the yard of The Lion in the High Street.[1] The earliest date recorded for The Kings Head is also 1734, when William Cheyney’s will provided twenty shillings to be paid annually from the rents of his messuage called the King’s Head to the church wardens of St Nicolas.[2]

In 1841 the innkeeper at the Lion seems to have been John Neale, and in the census there was a publican, William Flanagan, nearby, who was probably mine host at the King’s Head. Beyond the King’s Head to the east was John Preston a saddler and his family. The Prestons were also involved in coaching, with the Lion as one of their bases – taking passengers to and from Culham and Steventon stations, as shown in an advertisement from the Reading Mercury in August 1844, the year the Great Western Railway had opened its direct line from Didcot to Oxford. They also collected visitors from Abingdon station after the branch line opened in 1856.

In 1851, the two establishments were still separate, with James Taylor (probably) at the Lion, and Henry Allam at the King’s Head. In 1854 the latter was described as a ‘Commercial Inn and Posting House’.[3]

In the enumerator’s book for the 1861 census, the Lion is not indicated by name, but in the correct place in the return is an ‘innkeeper and brewer’ named James Taylor, aged 53 from Drayton, and his wife Francis, 48. They had four sons and six daughters all living on the premises, some in roles such as barmaid, ‘eating house keeper’, and assistant brewer, but one was a dressmaker and the younger ones were scholars. Two doors up was Eliza Allam, now aged 42 and widowed, but still an innkeeper. Soon after (around 1866) the two inns were amalgamated to become the Red Lion – as it was named on the 1874 Ordnance Survey map – and later, simply as The Lion.[4] The house between also disappears from the census, so it seems that this was when the gabled façade was created to give the new hotel its unified appearance.

The Lion seems to have benefitted from its position in the centre of town. Before the cattle market was formally established to the rear, traders gathered at the Lion to arrange deals.[5] It was also, as we have seen, a coach stop, and its rooms were used for balls and auction sales.[6]

In 1871 the Publican at the Lion was Charles Coombes, aged 41, born in Witton, Middlesex, with his wife Eliza, from Heythrop, Oxfordshire. There was one visitor, Elizabeth Robertson, aged 18 from Devon, perhaps a family friend, rather than a paying guest.

The 1881 census shows a Thomas Coombe as Hotel keeper at The Lion.

In 1891 the ‘hotel keeper’ was Walter Brawn, from Scotland, and again only staff were recorded there on census night.

In 1901 the census shows the landlord of the Lion to be Charles Coombs again, now a widower, aged 71, who was living there with some members of his family who were all employed in the business. The only ‘boarder’ was George Brown, a tutor, aged 24 from Wiltshire.

In 1911 the Lion was bought by William Henry and Alice Mayhead, and their story is told in the article on The Mayhead family & the Lion Hotel.

In 1936 the western part – the former Lion – was sold to F W Woolworth, who demolished it and in its place was built a store (No.19 High Street) and Pearl Assurance House (No.17), with Timothy White, a chemist, on the ground floor. The same fate almost overtook the adjacent King’s Head – which had continued to trade as The Lion public house – but following its closure in 1987 evidence of an early structure was found as the building was being stripped out and demolition work was stopped. By this time, however, the ground floor had been completely modernised, so the main features of the historic building can be seen only at first floor level. The passageway to the staircase is a reminder of the earlier passageway from High Street to White’s Lane and the cattle market behind.

The upper room has a remarkable roof structure, the earliest part of which dates from 1291, making it so far the earliest reliably dated domestic building in Abingdon. It is of a type known as a crown-post (Fig.4), an early form which uses a long horizontal timber – known as a collar purlin or crown plate – to support the collars of the roof trusses to prevent them tipping over (racking), which was a serious problem with the earlier common-rafter roofs. Two crown-posts survive – with carved octagonal lower sections; that at the far end is braced only to the crown plate; the other had four-way bracing to the collar and to the crown plate, though one of the braces has been removed.

Figure 4. Crown-post roof, showing rear bay and both crown-posts. The collar purlin is the long horizontal timber in the centre

© D Clark

The most striking feature of the roof, however, is the pair of curved scissor-braces which replaced the former crown post in the front bay (Fig.5). These were cut from the same tree, are moulded on the undersides and lapped across each other, looking for all the world like a timber version of the crossing piers of Wells Cathedral (1338). Even more surprising is that the timbers were felled in 1501 – long after this type of roof had been popular – most of the curved scissor-braces found in Oxfordshire roofs date from the early-mid fifteenth century, for example the smaller and partial version in the roof over the side gallery to Abingdon Abbey’s Long Gallery of 1455. And to add to the unusual nature of this roof is the fact that there are grooves all along the scissor braces, with some remnants of plaster within them – suggesting that the purpose of the new bracing was not for display but to support a barrel-vaulted plaster ceiling.

Figure 5. Scissor braced truss

© D Clark

This roof is within the left-hand gable as viewed from the street. In the right-hand gable is a seventeenth- or eighteenth-century plaster barrel-vault with a moulded cornice, obscuring the timber structure above. The timber frames of each part are separate structures.

The Lion/King’s Head is thus a remarkable survival of a late thirteenth-century building, probably having shops at ground floor level to catch people going through the passageway. The later transformation of its upper floor is unusual for its date and striking character.

© AAAHS and contributors 2020

[1] Smith, Jacqueline and Carter, John Inns and Alehouses of Abingdon 1550-1978 (Abingdon, 1989) p.114; Cox, Mieneke, Abingdon – an 18th century County Town. (Abingdon, 1999) p.79.

[2] TNA PROB-11-658-207

[3] Smith and Carter (1989) p.109.

[4] Taylor, M K ‘The Lion Public House, 15 High Street, Abingdon’ in South Midlands Archaeology 18 (1988) pp.117-121.

[5] Townsend, James (1910) A History of Abingdon (London, 1910) p.159.

[6] Townsend, James (1910) A History of Abingdon (London, 1910) p.168.