George Knapp was a leading citizen of Abingdon in his time, and we know more about his character and lifestyle than about most of his contemporaries. This is largely because of his long friendship with the diarist William Bagshaw Stevens who commented on many of their meetings and transcribed some of the letters they exchanged.[1]

The name of Knapp is remarkably prominent in the history of Abingdon. The family had its roots in Chilton, a village between Abingdon and Newbury, to which many of them would return to be buried. From 1680 to 1765, Henry, Thomas and John Knapp, grandfather, father and son, followed each other as town clerks. During this time, their cousin Richard was recorder from 1711 to 1716, and his son George from 1718 to 1732.[2] Another cousin George Knapp was working in Abingdon as a grocer. In 1753 he married Catherine Tyrrell from Kidlington and received with her a significant amount of property in Kidlington and elsewhere, including a lease on the site at the north of the Sheep Market (now the Square) in Abingdon known as the Corner House. This had previously been occupied by the Pleydell family, also grocers.[3] This George was Master of Christ’s Hospital in 1756 and 1752 and mayor in 1759 and 1767. The George Knapp who is the main subject of this article was the first son of the marriage, born in 1754.[4]

Young George was educated at Abingdon School and at first seems to have followed his father (who died in 1776) as a grocer in partnership with his younger brother Henry at a shop in West St Helen Street.[5] But newspaper announcements by 1788 show him as taking on financial functions, and at a date which remains uncertain he became a partner in the new banking enterprise of Knapp, Tomkins and Goodall with its headquarters on the north side of the High Street, close to its corner with The Square and just a few steps from his home.[6]

He was also pursuing a career in local politics. He became a secondary burgess in 1780 and almost immediately after was made a bailiff. He was chamberlain in 1790 and a principal burgess in 1791, and was mayor in 1792, 97, 99, and 1807. He was joined in the Corporation by his brother Henry who was mayor in 1794, 1805 and 1813. Strangely, he was never a governor of Christ’s Hospital, though both his father and his brother Henry were several times master.[7]

William Bagshaw Stevens had been George’s contemporary at school, and became Headmaster of Repton School near Derby. George features frequently in the diary he kept from 1792 till his death in 1800.[8] Stevens had often to visit Oxford, and would spend a day or two with George at his houses in Abingdon or Kidlington, or they would dine together at the Angel in the High Street in Oxford.[9] George’s unmarried sister Anne kept house for him. George, and sometimes Anne, regularly travelled to Manchester, and Repton was a convenient staging post for them. They had a brother Joseph who had settled in Manchester, but for George the main attraction was a Miss Keymore with whom he was carrying on a slow long-distance courtship. As Stevens had long and sarcastically predicted, the affair failed to prosper.[10]

Perhaps the most important revelation that the diary gives about George is his weakness for gambling. In 1792, he managed to lose £1300 in two sessions. “How I grieve for his destructive follies”, lamented Stevens.[11] He sadly summed up his friend’s character:

“ … a friendly good-humoured man, perhaps too good humoured. Not he the Shark but the Shark’s Prey. Pity that he should be such a Dupe to Gamesters. Without temper, skill or knavery, he is fool enough to believe himself a Match for Them. Ruinous Infatuation!”.[12]

Did he suspect that George was being cheated? And if so, was he right?

But George seems to have continued wealthy in spite of his losses. About 1800, his house on the Square was rebuilt in the newest and most prestigious fashion; it is now Barclays Bank.[13]

In parallel with his activities in local politics, George took an interest in national affairs. In 1789, there was a political crisis over the regency during the incapacity of George III. George Knapp was a member of a committee that arranged to send a declaration of support to William Pitt in his contest with the supporters of Charles James Fox. Among his six fellow committee-men were Joseph and William Tomkins with whose banking enterprise he would or had already become associated. Abingdon’s MP at the time, Edward Loveden Loveden, supported Fox. Nonetheless, the committee was able to get the signatures of 194 of Abingdon’s 232 voters. The leading citizens of Abingdon, George among them, were solidly conservative and did not share Fox’s radicalism and his distrust of the monarchy. [14]

In 1792, as the excesses of the French revolution became known, George, mayor at the time, formed a loyal association sworn to defend “the Constitution of Government by a King, Lords and Commons which our ancestors cemented with their blood” and to “maintain public order, submission to the laws, and the security of property”. Initial membership was twenty-three, all from among the leaders of Abingdon society and including four members of the Tomkins family representing the dissenters. They would “oppose all meetings of a seditious tendency” and suppress “those infamous publications whose object is to render the people discontented with a constitution which is the source of inestimable blessings to all”. [15] The main publication such associations had in mind was Paine’s Rights of Man which had appeared in the preceding year and had rapidly become a best-seller.

In 1794 the government instigated the formation of local volunteer forces throughout the country, a sort of Home Guard in case of a French invasion. Units would be autonomous, deciding their own membership, officers, training programmes and, especially, uniforms. Once more there was a committee of the great and the good, including George and his Tomkins associates. This was much to the amusement of his friend Stevens who wrote sarcastically:

“I am glad to hear of your splendid doings in my native town, and that the nurse of my childhood is to be defended by the gallant intrepidity of her own offspring. Peace I am afraid is yet at a distance so that you plumed warriors may caper again and again with your fair partners and dazzle them into love with your martial finery.”[16]

There was no sign, therefore, at this time of George being anything but a mainstream Whig, far from espousing any reformist principles such as those claimed by Fox. This would change radically, and it was almost certainly Stevens who was responsible. The manorial family at Repton were the Burdetts of Foremark, and Stevens was on intimate terms with them.[17] He was the mentor and confidant of his patron’s grandson Francis Burdett, and it was no doubt through Stevens that George met him. Francis was a moody and troubled young man, but he was charismatic, and would become leader of a strongly reformist faction in Parliament.[18] At some time which remains uncertain, George came round to Burdett’s views.

The political situation in Abingdon at the end of the eighteenth century was complicated. The town was in the sphere of influence of Sir Edward Loveden Loveden of Buscot in north-west Berkshire. He had been the town’s MP until 1796, but had then given up the seat in the hope of gaining a more prestigious county one, in which he had failed. He had been replaced in Abingdon by a government nominee, Sir Thomas Theophilus Metcalfe, with treasury money behind him. Metcalfe had spent most of his career making his fortune in India, and was a director of the East India Company. Control of the Company had until recently been an active political issue, and Metcalfe would be bound to support William Pitt’s administration which was generally favourable to it. The interests of Abingdon would be secondary.[19]

Loveden maintained his interest in Abingdon, and it was probably he who encouraged George to stand as a parliamentary candidate.[20] There are signs that George was already considering this during his mayoralty in 1799/1800. It was a year of frighteningly high food prices; the government was concerned and in a circular of December 1799 enjoined a standard bread quality that was supposed to reduce the proportion of the wheat extracted in milling and eke out supplies. George took the unusual step for the mayor of a small town of writing formally to the home secretary, the Duke of Portland, pointing out that this would be counter-productive since the bread normally eaten in Abingdon was in fact of a lower quality than that specified. He feared that the Berkshire magistrates would seek to enforce the measure in the county. He enclosed the calculations that went into the latest weekly Assize of Bread; prices, based on the price of grain coming to the local market, were at three times their level of two years earlier. He need not have worried; the county magistrates under the Earl of Radnor would take the same view.[21]

Before the end of his mayoralty at Michaelmas, George would write again to the duke, twice. Grain prices had risen even further, by almost half, and there was serious unrest. The Riot Act had been read. The situation had been managed with the help of troops stationed in the town and he was concerned that they might be moved away to deal with problems elsewhere. He asked that they should stay through the winter, or at least until the next market day. He enclosed with one of the letters a pamphlet which ‘had come into his hands’ and which he claimed, implausibly, not to have read. It advocated government control of grain stocks and prices.[22]

Grain supply eased somewhat with a good harvest in 1801 and peace returned to the markets.[23] George’s preferred policy was never adopted. But it may be that he was preparing his ground, and making sure that his name would pass under the eyes of some senior political figures.

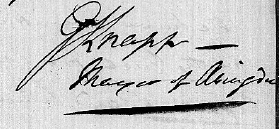

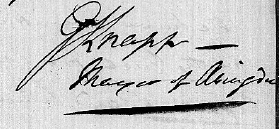

Signature of George Knapp(Reproduced by permission of The National Archives)

The Abingdon electorate numbered some 240 of whom 70, it was said, were open to bribery. Metcalfe was said to be ready to spend £3000 or £4000 on his campaigns, though Loveden thought it would need only half that to beat him. George would obviously have the support of his own family and friends, but also of the Abingdon dissenters whose leaders included his business associates the Tomkins. The dissenters were a major factor in Abingdon elections.[24]

The first step, necessary but not sufficient, was to ensure that the mayor, who would also be the returning officer in any election, was of the same political camp. The system was that all the town’s electors would make their choice between two slates each of two primary burgesses; the Corporation would then choose one from the winning slate to be the next mayor.[25] George Knapp and his friends managed to dominate the mayoral lists in this period. George himself was mayor in 1799-80 and was followed by another of his old schoolfriends, Thomas Knight. But an opponent, Edward Child, was in office at the general election of 1802, and Metcalfe won it by 111 votes to 102. George’s associate William Allder was mayor in 1803-4 and his brother Henry in 1805-6, but there were no general elections in those years. It allegedly cost £500 to put Thomas Knight again into the mayoralty in 1806 but he was unable to prevent another narrow victory, by 125 to 118, for Metcalfe.[26]

There was a further parliamentary election in May 1807, with Knight still mayor. The town was once more split down the middle between the ‘purples’ supporting George Knapp and the ‘blues’ for Metcalfe. This time, George won by seven votes (120:113) but only after Knight had disqualified nine that had been cast for Metcalfe. Metcalfe threatened to petition to have the election annulled, but did not.[27] George was also elected mayor of Abingdon in August, and regaled the populace with bread and cheese and ‘several barrels of strong beer’.[28] It is not clear how he manged to reconcile the demands of the two positions.

George had campaigned as the candidate for “freedom and independence” and portrayed his opponents as scheming to subject the town “to the domineering influence of a few individuals”. Independence was an electioneering slogan in many constituencies and implied the rejection of candidates like Metcalfe dependent on outside support and obedient to outside authority.[29] In a Parliament that was supposed to represent interests rather than individuals, the ideal candidate would be a local man looking primarily to the good of the town that sent him. George, also, was for religious toleration while Metcalfe was against toleration as conducive to ‘popery’.

We do not know when George’s connection with the reformer Francis Burdett began and it had not been emphasized in his election campaigns, but once he was safely in Parliament he showed himself as a devoted follower. Burdett was impatient and ahead of his time. When in 1809 he proposed a motion for parliamentary reform with all householders given the franchise this was seen as dangerously radical and most of his supporters deserted him. George was one of just fifteen members who voted in favour.[30] The reformists had more success when they concentrated their fire on particular instances of corruption in high places, whether real or invented for the purpose. In 1809, allegations by a rather disreputable MP named Wardle forced the resignation of the Duke of York as head of the army, in spite of the damage this would cause to the war effort against Napoleon.[31] Wardle was briefly a national hero. At a banquet of Berkshire personalities in his honour, George Knapp was praised as one of his supporters.[32] At another, in London, he was among the speakers.[33]

But by the time the weakness of the case against the duke had become clear, George was dead.

There is some mystery about his death, which occurred on 12 November 1809. According to the newspaper reports it resulted from head injuries sustained some days earlier by falling out of his gig.[34] Suspicion is aroused by the absence of any further information on the date, place or circumstances of the accident and the absence of any report of an inquest in London, Oxfordshire or Berkshire. George had added a codicil to his will as recently as 2 November, suggesting he may have known of a risk of death. The appearance is that something was being covered up.

George Knapp’s memorial tablet in the church at Chilton(Photo: M. Brod 2018)

Perhaps the most likely explanation is that George had died as a result of wounds received in a duel. Duels were frequent at that time, especially as a way of settling gambling disputes. A cover-up would suit the bank which might otherwise find its credit impaired, and the other party to the duel who might find himself in court, though acquittal in such cases was certain. Whatever the truth of the matter, further information is now unlikely to emerge.[35]

The Knapp chest tombs by the south door of Chilton church. George’s is the middle of three.(Photo M. Brod 2018)

George joined his forefathers in the churchyard at Chilton on 18 November. Their chest tombs remain just east of the south door. His brother Henry moved seamlessly into his place at the bank.[36] The bank survived, and it was Henry’s son, also Henry, who was in control when it finally succumbed in the financial crisis of 1847.

George never married, but two “natural” daughters, Anne and Harriet, were recognised in his will and well provided for.[37] The will of their aunt Anne who died in 1839 shows that both women were unmarried and living with her at that time.[38] Nothing is known of their mother.

Much later, the novelist Emily Bowles (1818-1908) recollected the three Misses Knapp whom she will have known as a girl:

“The aunt, a somewhat fussy old lady, like a well-fed purring tabby cat with more than one double chin and wearing caps which were absolute mountains of ribbons and lace and much beflounced gowns of rich silk, for she was a woman of some wealth who like to live comfortably. The two nieces were not so pleasant to look at, tall, lank figures, extremely plain, but with a most kindly expression, wearing no caps or “fronts” but only their own hair in corkscrew curls and side-combs to mark the fact that compared with their aunt they were jeunes encore. Both of these sisters talked at once, and as fast as possible, or if one was ever allowed to begin a sentence independently the other invariably finished it with variations. This triad of ladies were often called in to make up a table or a rubber, and in this last contingency only, were ever known to practice silence.” [39]

George Knapp seems to have led the life of a wealthy bachelor of his time, with his two houses, his gambling, his mistress or mistresses, his frequent travel for social or family reasons. We are lucky to have the personal details on him that Stevens’ diary gives, and would wish to have more. But it is his short parliamentary career that is of greater interest, giving a glimpse of conviction politics in a period of what by modern standards was outrageous corruption and yet when the country was, on the whole, tolerably well governed. Speaking of himself shortly before his untimely death, George said “As an individual, I am of no kind of consequence in the Senate … but I am at all times ready to do what I think is for the good of the country; and I am as independent in principle and in conduct, as the first man in the House of Commons.”[40] Could any of today’s members of Parliament say as much?

© AAAHS and contributors 2018

[1] Brogan, H. (2004-09-23). Stevens, William Bagshaw (1756–1800), poet and diarist. Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. Retrieved 25 Jun. 2018

[2] A C Baker Historic Abingdon: Fifty-six Articles (Abingdon, 1963), pp 17,18,91, 108; Abingdon Town Council Minutes to 1686, fo. 239v.

[3] For the Kidlington property, see Mrs Bryan Stapleton, Three Oxfordshire Parishes (Oxford Historical Society Vol XXIV, 1893) pp. 46, 48, 195; for the Abingdon lease, Abingdon Town Council, Leases (17 Jan 1757); Corporation Minutes Vol II, fo.28; Abingdon Buildings and People website: https://www.abingdon.gov.uk/history/people/pleydells (accessed 6 July 2018), https://www.abingdon.gov.uk/history/buildings/2-and-3-square (accessed 19 Sept 2018).

[4] Oswald Greenway Knapp, M.A., A History of the Chief English Families bearing the name of Knapp (privately published, 1911), p. 56.

[5] Mieneke Cox, Abingdon, an 18th Century Country Town (Abingdon, 1998), p. 177.

[6] Oxford Journal – Saturday 01 March 1788 p. 2; Benjamin Read’s survey of Abingdon, 1838, Berks Record Office, D/EP7/163.

[7] Knapp, History … name of Knapp, p. 56; Bromley Challenor, Selections from the records of the Borough of Abingdon (Abingdon, 1898), appx xlvi; Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 6 Sept 1783, p.3; C D Cobham, A monument of Christian Munificence, 1873, Appendices. Thanks are due to the Master and Governors of Christ’s Hospital for access to their archives, from which George Knapp is absent.

[8] Georgina Galbraith (ed), The journal of the Rev William Bagshaw Stevens (1965).

[9] http://www.oxfordhistory.org.uk/high/tour/south/angel_hotel.html (accessed 4 August 2018)

[10] Galbraith, Stevens, pp 110, 212.

[11] Galbraith, Stevens, p. 92.

[12] Galbraith, Stevens, p.45.

[13] Refer to forthcoming article on The Square.

[14] Oxford Journal – Saturday 31 January 1789 p. 3; James Townsend, News of a Country Town (Oxford, 1914), p. 102n; http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1754-1790/member/loveden-edward-loveden-1750-1822 (accessed 22/07/2018).

[15] Oxford Journal – Saturday 15 December 1792 p. 2.

[16] Oxford Journal – Saturday 10 May 1794 p. 2; Galbraith, Stevens, p.212; Austin Gee, The British Volunteer Movement 1794-1814 (Oxford, 2003), passim and pp 162-3, 189.

[17] Galbraith, Stevens, p.109 and notes.

[18] http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/burdett-francis-1770-1844 (accessed 14 June 2018).

[19] David R Fisher http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/metcalfe-thomas-theophilus-1745-1813 (accessed 25 June 2018); Michael J Turner, The Age of Unease: government and reform in Britain, 1782-1832 (2000), pp. 23-7, 31-2.

[20] David R Fisher in http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/constituencies/abingdon (accessed 25 June 2018).

[21] The National Archives (TNA), HO 42/51/202 fols 296-7; HO 42/49/38 fol 85; HO 42/49/43 fols 92-4.

[22] TNA, HO 42/51/201 fols 496-7; HO 42/51/209 fols 514-25. The pamphlet is J. Malham, The scarcity of grain considered (Salisbury, 1800).

[23] For long-run grain prices at Winchester, see International Institute for Social History, ‘Monthly grain prices in England, 1270-1955’, http://www.iisg.nl/hpw/poynder-england.php (accessed 20/08/2018)

[24] David R Fisher in http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/constituencies/abingdon (accessed 25 June 2018).

[25] James Townsend, News of a Country Town (Oxford, 1914), pp 8, 114-5, 119.

[26] Oxford University and City Herald – Saturday 30 August 1806 p. 3.

[27] David R Fisher in http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/constituencies/abingdon (accessed 25 June 2018).

[28] Oxford University and City Herald – Saturday 05 September 1807 p. 3

[29] Frank O’Gorman, Voters, Patrons and Parties; the unreformed electorate of Hanoverian England, 1734-1832 (1989), pp 259-285 esp. pp 272, 272, 280n.

[30] [30] David R Fisher, http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/knapp-george-1754-1809 (accessed 25 June 2018).

[31] Ian R. Christie, Wars and Revolutions: Britain 1760-1815 (1982), p. 302; Turner, The Age of Unease, p. 121.

[32] Oxford University and City Herald – Saturday 22 April 1809 p. 3

[33] David R Fisher, http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/knapp-george-1754-1809 (accessed 25 June 2018).

[34] Oxford Journal – Saturday 18 November 1809 page 3.

[35] J C D Clark, English Society 1688-1832 (1985), pp 106-18.

[36] Oxford Journal – Saturday 25 November 1809 p. 3

[37] The National Archives, PROB 11/1509

[38] The National Archives, PROB 11/1920

[39] Caroline Cannon-Brookes ‘The Bowles Family of Abingdon’ (Lecture transcript), Aspects of Abingdon’s Past, Vol 6, (St Nicolas, Abingdon, 2008).

[40] David R Fisher, http://www.historyofparliamentonline.org/volume/1790-1820/member/knapp-george-1754-1809 (accessed 25 June 2018).