Oswald Couldrey

1882 - 1958

Biography

Oswald Jennings Couldrey is Abingdon’s best-known twentieth-century artist. He was born into a local family of seed merchants and agricultural suppliers which for several generations had included musicians, scholars and teachers, especially at Abingdon School, then Roysse’s School. Oswald went up to Pembroke College, Oxford as an Abingdon Scholar, then gained a teaching qualification and entry to the Education Service of the Indian Civil Service, living and working in India from 1909-1919, for eight years as Principal of the Rajamundry College of Art in Andra Pradesh.

Couldrey responded passionately to the landscapes, art and music of India, became a Guru to his students and is acknowledged as a significant influence on the renaissance of Indian art in Andra Pradesh in the early twentieth century. Tragically he lost his hearing and was obliged to retire and return to England at thirty-six.

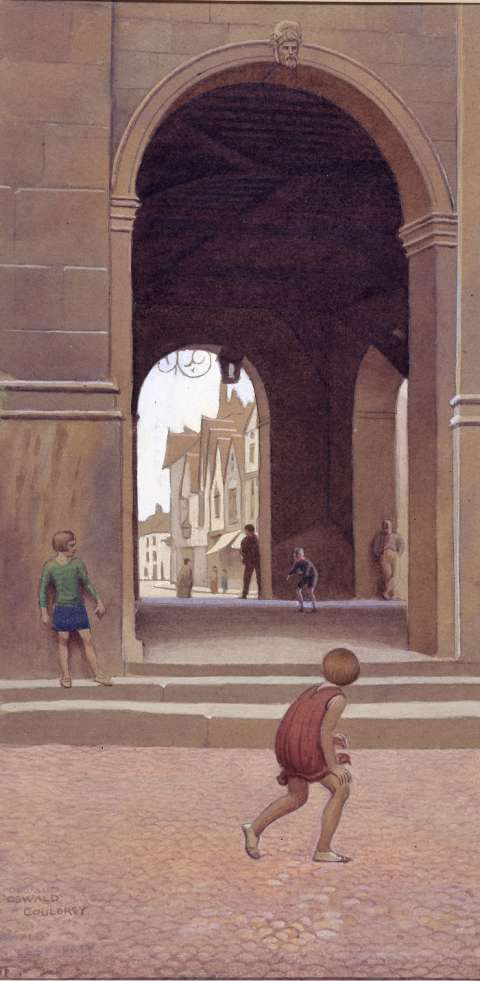

St Nicholas’ Church and Abbey Gateway, 1941, Watercolour, signed. This image of the Marketplace at the time of World War II seems unnaturally quiet and free of vehicles.

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum (OXCMS:1980.191.488)

Couldrey considered himself a poet and a writer rather than an artist. His poetry, short stories and a major work, South Indian Hours, published over fifty years, are autobiographical and recount his frustrations. His immense vocabulary and extreme erudition make these less accessible than the pictures into which he channeled his energies from the 1930s, creating some of Abingdon’s most iconic images.

Lauren Gale

© AAAHS and contributors 2017

Figure 1. Portrait of the artist as Guru. From a photocopy of the frontispiece of a book by Kamesware Rao, a scholar of Telugu literature: “To Guru dev. O.J. Couldrey Esq., M.A. (Oxon.) Retd. Principal, Govt. Arts College, Rajamundry, a casual remark made by whom in the lecture room converted me to my mother-tongue, I – with his kind permission most worshipfully Dedicate this humble life’s work of mine – his old student, B Kameswara Rao.”

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum)

Origins and education

Oswald Jennings Couldrey was Abingdon born and bred of an extensive local family, traced in the area back at least to the eighteenth century. By the nineteenth century family members had established themselves as merchants dealing in agricultural supplies, with homes and premises in East St Helen Street and at other town locations close to the Market Place. Sources mention seedsmen and maltmen (for example John, Solomon and Thomas Couldrey, maltmen, in St Helen’s church Register); a relative who figures in the Burgess Roll for 1836 was a seedsman, and Oswald’s grandmother (Rebecca Emma Knight) was a seed saleswoman. The 1891 Census records Oswald living at 47 East St Helen Street with his father Frederick, described as a solicitor’s clerk, and his grandmother.[1]

For at least four generations significant numbers of family members had shown an outstanding ability in the arts both as teachers and practitioners; these talents must have been encouraged and supported at home and in the church community. To quote The Abingdonian, “Couldrey’s father was organist at St Helen’s Church for 60 years, and three uncles were organists: Thomas at Swindon, another, Robert, at Windsor, both as Organist and a Music Master at Eton, and the youngest, Charles, for some time Organist at St Nicholas. Moreover his great-grandfather who was Writing Master at Roysse’s School was Organist at St Helen’s for 36 years.”[2] At Abingdon School, formerly Roysse’s School, sons of the family both attended and taught as music and art masters, and a daughter taught music. Altogether fourteen Couldreys are listed in the school’s Register.[3] Oswald’s two sisters (Margaret and Dorothy) together ran a junior school in the town (in Conduit Road, shown in Fig. 8), and at least one of them was a performing amateur musician.[4] Oswald’s background was not a particularly wealthy one, but he had inherited the family’s strengths in the arts and in education, and his own education was facilitated by academic scholarships both at school and university.

At Abingdon School he was a Junior Scholar, a Scholar, and a memorable figure in extra-curricular life: the School magazine describes him as editor-in-chief and illustrator of the Dayboy Comet, which ran to three issues in 1900, and he rowed for the School team.[5] At School he met the later war poet and author H(arry) Willoughby Weaving, more successful as an author than Oswald and always admired by him. Weaving was three years Couldrey’s junior, the same age as his younger brother Bernard James who entered the School in 1897 and died there that autumn; possibly Weaving as well as Oswald was affected by this tragedy. Harry and Oswald coincided at the School from 1898 to 1901, were both Scholars at Pembroke College and both in Oxford from 1905-1909, remaining in touch for many years.

Oswald resided in Abingdon all his life apart from six years of higher education, first as an Abingdon Scholar at Pembroke College, Oxford, then for a further qualification in teaching, and eleven years in India with the Education Service of the Indian Civil Service (ICS). At Oxford he read the Classics, studied ancient languages, and excelled as an oarsman; according to one of his Indian students Couldrey also swam competitively while at Oxford.[6] He matriculated at Pembroke as an Abingdon Scholar in the Michaelmas term of 1901, obtained a 3rd class in his moderations exams in 1903, a 3rd class BA in Litterae Humaniores (Classics) on 9 November 1905 and his MA on 17 December 1908.[7]

Figure 2. Pembroke College’s Torpid eight, 1902. Oswald is seated in the middle row, left of centre.

(Courtesy Pembroke College Archives)

At the end of his education he had acquired the learning, attitudes and interests of a gentleman, but lacked a gentleman’s resources, and so alongside other similarly-placed young men of his time in search of an appropriate career, he applied to the Indian Civil Service. Here, while lacking the First Class degree thought necessary to embark on the mainstream ICS career path, he gained entry to the Indian Education Service, which involved qualifying as a trainee teacher probably before the entrance examination as well as further study in eastern languages afterwards.[8]

His Art

Figure 3. ‘The Old Guildhall’, 1936. Watercolour.The baroque Abingdon County Hall of 1682 is seen through its arches as if by the children playing below it.

(Courtesy of Abingdon County Hall Museum (OXCMS: 1980.191.484))

Couldrey’s surviving artworks, reproductions of which illustrate many of his publications, are displayed at Abingdon County Hall Museum, curated at Oxfordshire County Council’s museum store at Standlake, held in the archives of Abingdon School, and in private ownership. They form a significant collection created over many years, although they were probably felt by him to be subsidiary to his written work.

Dating from his youthful years before India, the lively sketches preserved in Abingdon School’s archives were illustrations made for the School’s Dayboy Comet, of which he appears to have been the principal contributor and driving force: four issues from the years 1895 – 1900 have both literary and artistic contributions by Oswald. His sketches of the human figure show the influence of Art Nouveau book illustrators like Aubrey Beardsley, and he continued to use this drawing style for figure sketches, especially female, adapting it to the graceful draperies and movements he observed in India.

Figure 4. Cover illustration and Frontispiece, Thames and Godavery (First and second editions, Oxford 1921). Many of Couldrey’s book illustrations are in the Art Nouveau style.

(Courtesy Abingdon School library)

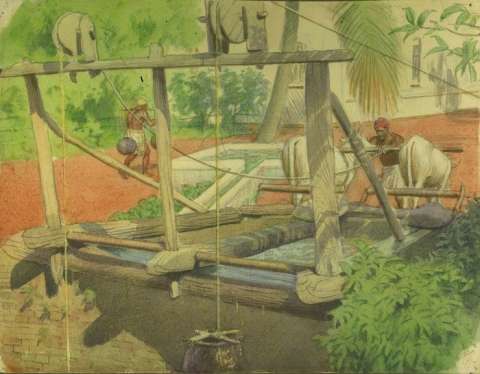

In India, sketches, watercolours and drawings in coloured pencil illustrated the extensive diary notes of Couldrey’s time there, and served as prompts for his writing – he may have intended these notes for future publication, and perhaps some survive within the short stories. Some of the pictures were part of painting expeditions, when he was sometimes accompanied by his students.[9] About 50 of these, dating to 1909-19, were bound into an album entitled Indian Memories painted by Oswald Couldrey.[10] These pictures capture the languorous and sometimes ambiguous quality of the South Indian landscape and its balletic inhabitants. They divide into three geographical sequences probably relating to three or more painting tours with his students: (1) from the artist’s own garden and neighbouring houses and yards down local roads to the town of Rajamundry and its southern suburb Dowleishwaram, then onto the banks of the Godavery River (1 – 31); (2) beauty spots and architectural highlights to the north of Rajamundry, from Pattisam to Simhalacham and Waltair about 100 miles away (32 – 41); and (3) a much longer route to the southwest, to Madras (Chennai) and Madura in Tamil Nadu, ending at a hill station in the Ghats on the borders of Kerala (42-53); others were painted in Kashmir and the Sind Valley in northern India, the artist’s resort, he says, before he was able to appreciate the beauty of his own surroundings in South India (South Indian Hours I, 54-59).

Figure 5. Bucolic Watercolour painted on a ‘March morning looking E. Mango tree 40 yds E of the SE corner of my front garden’ in Rajamundry.

(Courtesy Abingdon Count Hall Museum. OXCMS:2007.81.1))

Figure 6. A Well in a Garden Couldrey was fascinated by South Indian wells. This fine example was in the garden of a neighbouring ‘big house…which is seen behind.

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum.(OXCMS:2007.81.6).)

Couldrey seems to have intended eventually to publish these as illustrations of an account of South Indian monuments (one of his pictures, of Devagizi Citadel, is described as ‘Illustration for Idols of the Deccan’: Oxfordshire Museum Service OXCMS : 2003.4.8), but this ambitious project resulted only in two published articles that we know of, appearing in the 1940s in the Geographical Magazine after he was obliged to leave the country, on rock sculpture of the Deccan and the rock temples of Ajanta.[11]

The landscape paintings of his middle and later years in England appear to have been his principal occupation on holidays when he visited friends or stayed at the seaside, often in the company of Enid Naylor – his former bank manager’s orphaned daughter whom he had befriended after the premature death of her parents – and Enid’s young daughter Pauline Bagg. Pauline may be the only remaining person who knew Oswald well. Although still a teenager at the time of his death, Pauline’s astute youthful observations and collected mementos, generously shared with successive Abingdon museum curators, reveal a different side of the artist from the bitterly disappointed persona of his poetry. She recalls him as a Bohemian personality, a lover of life, good company, wine and women (even if unable any longer to hear the song), confirmed by Bapiraju’s recollection of his teacher at home in his garden: “He liked Uppada dhotis and upper cloths. He used to wear only them while at home. Sitting among the flowering plants around his bungalow at Alcott gardens (in Rajamundry), and putting on an Uppada dhoti and a shiny Uppada kanduva (upper cloth) on his fair chest, he looked to me like a God descended onto the earth!”[12] He was no businessman – unlike his slightly older Oxfordshire contemporary and fellow member of the Oxford Art Society, the landscape artist JA Shuffrey, he appears to have made no serious attempt to market his pictures, although he exhibited at the Royal Institute of Painters in Water Colours in 1927 and with the Oxford Art Society in 1928 and 1929.[13]

Figure 7. The Old Bathing Island, Abingdon. Watercolour, signed and dated August 1936. Remains of the concrete quay from which young men and women are diving and climbing in and out of the river may still be seen just upstream from Abingdon Bridge. The era of this idyllic picture, before the outbreak of World War II, is poignant.

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum. (OXCMS:1980.191.493).)

Figure 8. Conduit Road, Watercolour, signed and dated Abingdon 1937-42. A dynamic vision of girls of eleven or twelve cycling, walking and running out of the schoolyard (Jones, Gilmour and Henig,Treasures of Oxfordshire 2004, 81A).

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum (OXCMS:1980.191.491).)

Couldrey would never know that his pictures of Abingdon between the two World Wars would become iconic; their existence at all is the result of a freak and tragic illness, cutting short the Indian adventure. Gifted in writing, painting and music but especially as a teacher, it is impossible to surmise what he might have achieved had he been able to remain in India for the balance of his career. One of his students alludes to his work towards major publications on South Indian sculpture, for which he was amassing his own illustrations. We are fortunate to have some of these, as well as the fifty-plus English pictures in Abingdon County Hall Museum’s collection, and look forward to a more detailed publication.

His Writing

Couldrey would have been surprised to hear himself described as the town’s best-known twentieth-century artist, as he always aspired to be, and regarded himself as, a poet and writer, and took writing very seriously. Seven books were published between 1914 and 1959: The Mistaken Fury and other lapses (Oxford, 1914), Thames and Godavery (Oxford, 1921), South Indian Hours (London, 1924), Triolets and Epigrams (Abingdon, 1948 or after), The Phantom Waterfall (Abingdon, 1949), Sonnets of East and West With Other Verses (Abingdon 1951/2) and Verses over Fifty Years (posthumous publication, Abingdon, 1959). Of these, two of the three prose publications, South Indian Hours and The Phantom Waterfall, are masterful – the first a flawed masterpiece but the second a polished one and probably the most widely read during his lifetime.

South Indian Hours is a substantial prose work in three parts, documenting his adjustment to India and the period of fulfilment as Principal at Rajamundry College of Art, before an unforeseen return to England in a debilitated state in 1919. Parts I and II were written joyously in the first flush of a lifetime adventure, painting a verbal picture of an intimate acquaintance with the South Indian landscape and seasons, frequently observed through the lens of his own childhood in Abingdon and the surrounding countryside. Couldrey was fired by the sensuality of the architecture (“high tiara-towers of Dravidian temples”, “stone pools framed with stairs and crowned with pagan cloisters”), the landscape (“broad plains and clear horizons wrung with singular and sudden hills”) and especially the people who inhabit it (“bare brown limbs of Southern labourers, intellectual faces also, pencilled eyebrows, dark-set eyes adream with unfamiliar creeds and calm with remote philosophies”). From the time of his arrival on the banks of the Godavery estuary on the east coast of India south of Calcutta, he quickly found things his emotions could relate to, bonding deeply with the Godavery river, as he had with the Thames, with the timelessness and spiritualism of local life, and with the role of art and literature teacher and intellectual mentor to Hindu schoolboys of the Brahmin caste.

Part III of South Indian Hours strikes a more sombre note following dramatically changed circumstances. Couldrey’s adventure was cut short and he returned to England unwell, losing his hearing and forced to retire. It is shocking to compare a photograph taken after his return with those of the confident young oarsman of twenty years earlier – unemployed and disabled in a rapidly changing society, dependent for contact upon whatever family members and old school friends remained and were available. Perhaps one of these suggested lecturing (his talk on Indian Gods to the Abingdon Literary and Debating Society in 1924 was complimented in The Abingdonian), but he admits ruefully to a former Brahmin friend that he hopes “he is now doing a brisker trade in spells and absolutions than I in lectures”.[14]

Comparing himself, with his pre-war classical education and old-fashioned scholarly mentality, to the Brahmin, was apt. The life had now begun of a prematurely retired minor government official turned amateur artist, the ordinary resident of a small town, with a greatly reduced ability to communicate, cut off from the enjoyment of music (the family passion) and presumably on a relatively meagre pension. So it is not surprising that Part III of what was to remain his only major piece of published writing exudes a chill, and seems a forced attempt to wrap up the earlier reminiscences into a volume that would sell. To create a marketable package, three sections were now appended on some obvious areas of potential popular interest and curiosity – the castes, hunting and the history of South India – almost certainly on a friend’s or publisher’s advice; given his well-described distaste for hunting this could hardly have been his own choice. Couldrey’s personal experiences of Indian society, including his attempts to buck the Indian social system and its resulting rebuffs, plus a delightful description of a sister’s Hindu wedding contributed by his student Bapiraju, give interest to the caste chapter (‘The World and the Flesh’), and the hunting chapter (‘The Fringe of the Jungle’) must at least have startled readers of the period by the author’s evident dislike of killing things; the same distaste is expressed in ‘Confession’ in Thames and Godavery. But the history chapter (‘The Far Past’) is the shortest of the three, dry and impersonal and suggests why Couldrey may have failed to excite as a lecturer on this subject.

Appearing twenty-five years later, Phantom Waterfall is a book of eighteen short stories, each illustrated by the author’s pen-and-ink drawings made while in India. These stories, all set in India, are vignettes describing interactions between Englishmen in India, ‘Anglo-Indians’ and Indian natives. The nine short stories published between the wars in literary journals are charming and full of delightful description and youthful idealism, but seem immature in outlook when compared with the other nine previously unpublished but masterful stories, either written or rewritten in maturity, which seem more personal and reveal a deeper perception of social context. ‘The Abduction of Sita’ concerns a Raja’s invitation to a young director to bring a production of Othello to his palace in the hills, and reminds us of the author’s passion for theatre as a young man.[15] Based upon his experiences of teaching Shakespeare and staging yearly productions at Rajamundry Arts College, it abounds with the social and organisational dilemmas that must have been involved in these productions; the two-day journey to a Maharaja’s remote palace in the hills glows with passion for the sights and sounds of the south Indian countryside (“The bosky cones and crags of the red foothills, redder than ever in the sunset, began to change places about us as our caravan of carts wound jingling and creaking among them. I can hear still how the staccato shout of my palankeen-carriers, that curious musical gasp or grunt of theirs that runs up and down the line like a primitive scale played on a xylophone, jangled with its own echoes and the softer but more voluminous noise of innumerable doves.”) ‘The Vindication of Calliper’ describes the frustration of a relationship with an occasional colleague of unusual intellect and creativity, of Couldrey’s age and independent school and Oxbridge background. The narrator craves his companionship (“the Indian hinterland favours a variety and an intimacy of personal relationship which is remembered later with regretful affection…he looked forward with a quite inordinate eagerness to meeting Calliper, who had written a play, and was also said to be a philosopher”) but Calliper plays cat and mouse with him, preferring the maintenance of his mystique to genuine communication.

The younger writer of South Indian Hours would have found it unthinkable to express the themes explored in ‘The House in Building’, ‘Asprisya’ and ‘Parkin’s Prayer’: in the first of these, the possibility, and in the second and third the actuality and consequences, of sexual relations between an ICS officer and a native Indian girl. The first of the women in question is described as a self-confident young upper-caste Indian whom the listener to the main narrator “had fallen head over heels in love with …by report, and bad report at that” (‘House’). The second is a “Eurasian Doctor’s daughter… a European in the Indian mofussil (remote provinces) almost never sees anything resembling a marriageable damsel of his own race, which may not be for years together” (‘Asprisya’). The third is a mission upper school girl, Susanna, ”almost black; black but comely, like the Shulamite… her face, like a picture by Greuze, retained in early womanhood the round freshness of childhood, but her stature was tall, as Indian women account tallness, and the shapely ripeness of her young body was apparent even in the long-sleeved and rather heavily swathed costume enjoined by her religion… Christianity, in India” (‘Parkin’s Prayer’). This is his only publication where the sexual attraction of Indian women is uninhibitedly described. Even more intriguing is the partly-shared secret revealed in ‘Fancy’s Breakfast’, a story recording an episode where the narrator leaps into a well in an unsuccessful attempt to rescue a suicidal young Indian woman (“I remarked instinctively, as a bachelor will, the succinct shapeliness of her slender body and the beauty of her naked thighs”). Oswald sometimes adduced the rescue of a native child from a well and the resulting ear infection to account for his illness, deafness and retirement; perhaps that experience is the background to this story.

Figure 9. ‘Nausicaa’, 1952. Painted close to the end of his life, a theme from his youthful book The Mistaken Fury (‘Letters from the Phaeacian Capital’) is more fully and sexually developed.

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum (OXCMS:2003.4.11).)

The volumes of poetry demonstrate Couldrey’s immersion in a classical and Christian education and the struggle with his own feelings of loneliness and bitterness in a changed and changing personal and external world. The poems are at once biographically enlightening and tragic to read. Several poems stand out, especially ‘The Land of Beulah’ (Thames and Godavery, 14), a compassionate portrait of a woman in extreme old age, perhaps his own grandmother, with its Biblical and Shakespearean themes and subtle rhythms reminiscent of Greek lyric poetry.[16] The contents of all four published volumes of poetry are personally revealing and make no attempt not to be. Triolets and Epigrams is a good example.[17] Relationships with like-minded men, people who could appreciate poetry, are key. Poems speak of his friend Willoughby Weaving with emotion. Two concern Pewet, Weaving’s childhood Abingdon home, To Willoughby Weaving, 85, lamenting a new owner’s change of name to Prospect Park in 1930 – “how the world grows dark”, a second its demolition to make way for the airfield (Lament for Pewet 1944, 86) and the third expressing sadness at their separation (also entitled To Willoughby Weaving, 37), describing “Lovely sounds forgotten. Long/ Reft and starved of Life’s refrain,/ In your verse I hear again!/Bells and laughter, scythes and rain,/ Leaf and wave and woodland song.”

His deafness is the theme of at least nine other poems on pp. 27 – 36, most pathetically Tantalism, 35: “My friends are put away from me. As when at windowed revelry a wistful neighbour peers unbidden”. He is bitter too about his lack of success (pp 61-3, 65, 68), especially in Perfect Witness, 63 – “Pictures that nobody buys, Poems that nobody reads” and Query, 68 – “Who will read my rhymes? Who will pay my wages?” and writes unhappily of his middle age in On being forbidden certain innocent pleasures about the time of his forty-eighth birthday, 26 ”it seems a very curious thing that forty-six may have his fling and forty-seven may not’, and in A Species of Eternity, 39. The Second World War is tedious (“Till war’s and want’s horizon clears I long and wait”), Hope Deferred, 66), Abingdon’s development offensive (The Burden of Abingdon, 78, Rye Farm Elms, felled 1940, 84), and motor vehicles an “Abomination” (pp. 72-4). There are nine poems concerning, mostly disparagingly, love and the company of women (“grey loneliness or nuptial chains”, Dilemma, 90; of lovers, “they cling as if they fear”, Lovers in the Dark, 94; “Never the time and place and the loved one, all together!”, Mostly Browning, 57, although in Release, 93, “The youthful shapes that please my eyes No longer plague my heart”). As the ageing poet looks about him, what he sees is that things are getting worse. (How the World Worsens, 14, and Revenant, 80).

Couldrey died at his home in St Michael’s Avenue, Abingdon, on 24 July, 1958.

Figure 10. Broad Street, Abingdon, 1940. The playful piglets being driven to market are one of many humorous touches the artist introduced into his townscapes of Abingdon.

(Courtesy Abingdon County Hall Museum.)

Lauren Gale

© AAAHS and contributors 2017

[1] Letter dated 15 October 2001, at Abingdon Museum, from Bob Couldrey. A Couldrey family tree at the Museum records a seedsman, Adam C Couldrey, in the Burgess Roll for 1836.

[2] The Abingdonian Vol 3, No 9 (September 1948) p. 97. With grateful thanks to Sarah Wearne, Abingdon School Archivist, for this and the following School information.

[3] Nigel Hammond, A Register of Old Abingdonians 1563-1947. This online publication may be found on the Abingdon School website.

[4] The Abingdonian, Vol 6, No 14, (May 1925), pp. 209-10.

[5] The Abingdonian, Vol 10. No (6 September 1958), p 291.

[6] Rowing: The Abingdonian Vol 6, No 26 (May 1929), p. 401; Swimming: Adivi Bapiraju,‘Master Oswald Couldrey’, Sec 2, in Kinnera (Madras), October 1950 (translated by K B Gopalam).

[7] I am grateful to Amanda Ingram, Archivist, Pembroke College, Oxford, for this information as well as the photograph reproduced in Fig. 2.

[8] Charles Allen (ed), Plain Tales from the Raj. Images of British India in the Twentieth Century, (1975, Charles Allen).

[9] Adivi Bapiraju, ‘Master Oswald Couldrey’, Sec 3.

[10] Lauren Gilmour, ‘Oswald Couldrey, Abingdon Artist, and the Indian Renaissance’, in Henig and Paine eds, Preserving and Presenting the Past, BAR British Series 586 (2013) pp. 85-101.

[11] The Abingdonian, Vol 9 No 3 (September 1948), p. 97.

[12] Adivi Bapiraju, ‘Master Oswald Couldrey’ Sec. 3.

[13] Lauren Gilmour, Margaret Shuffrey, J.A. Shuffrey 1859-1939. An Oxford Artist’s Life Remembered, (Rural Publications 2003); The Abingdonian Vol 6 No 20 (May 1927), p. 306; Vol 6 No 25 (December 1928), p. 387; Vol 6 No 28 (December 1929), p. 436.

[14] The Abingdonian Vol 6 No 13 (December 1924), p. 204.

[15] I am grateful to Pauline Bagg for sharing her considerable evidence of Couldrey’s love of the theatre.