When Roger Amyce made his survey in 1554, he or his clerk walked down Boar Street (which is now Bath Street) and turned right at the Sheep Market into Ock Street. The Sheep Market is now The Square. Where he turned, he noted a tenement with a garden and appurtenances “iacens in angulo” – “lying in the corner” – which would be known for centuries after as the Corner House.

Extract from Amyce’s Survey showing the Corner House as property of St Helen’s Church.

“The wardens of the parochial church of St Helen hold a tenement lying in the corner with garden and appurtenances in the tenure of John Meadowe, yielding per year for an obit in the Church of St Helen – xviii s.”

Reproduced by permission of The National Archives

There was something unusual about the Corner House. Unlike its neighbours, it doesn’t seem ever to have belonged to the abbey. It had been given by some pious donor to St Helen’s church to finance an obit – an annual prayer on the anniversary of someone’s death. The property was among those granted by the Crown to the new Corporation when Abingdon got its charter in 1556. It was described as “our tenement with the appurtenances situate in the corner of the north side of the Ock Street aforesaid, and one garden with the appurtenances now or late in the tenure of John Meadowe or his assigns”.[1] This account attempts to follow the history of the plot, the buildings on it, and the residents who lived and in most cases carried on their businesses there.

The plot was obviously of significant size although its eastern boundaries did not then extend as far into Bath Street as they do today. Its rental value was given as 18s per year (for currency values see glossary under ‘pounds, shillings and pence’). We know its later history from Corporation leases. Richard Wright had it at 23s 4d by 1580, and Richard Bowlls by 1586.[2] And by 1600 it must have been extended westwards by incorporating two neighbouring tenements which were where the present Barclays Bank is at 2 The Square. These two tenements were noted by Amyce as being former Abbey properties and having rental values of 12s and 8s respectively. The latter of them had earlier also been leased by John Meadowe. Thus by 1600 the site was bigger than it had been in Amyce’s time and there seem to have been three distinct holdings on it. These were leased separately, sometimes but not always to different people. Humphry Bowlls, presumably a son of Richard, had a little room and a shop, each with a chamber over; and John Heath, fuller, had a shop with a loft above. This shop, and possibly also that occupied by Humphry Bowlls, was separated from the main building and on the east side of the messuage. Humphry Bowlls’ rent was 20s, and it appears that Heath paid 14s.[3]

By 1605, when the main lease was taken over by Peter Stevens, the rent had increased from the 18s paid by Meadowe to 28s; in 1616 it passed to Christopher Willisby and in 1618 to John Steed. There was a period when Steed seems to have had responsibility for the whole property, and sometimes he and sometimes the sub-tenants took out the leases for the smaller apartments. By 1618, Humphry Bowll’s widow was occupying the apartment that had been used by John Heath, and was followed there in 1645 by Thomas Bowlles, barber, presumably her son.[4]

The old Bowlles lease at 20s had gone in the meantime to Richard Gillett, a man with money problems. As part of his contract with the Corporation, Steed was to exercise some sort of guardianship over him. He was to pay off a £4 debt to John Richardson, and “keep in his hand” £5 which he had lent to Gillett and presumably had been repaid. John Richardson was a serjeant at mace of the borough, and the debt will most probably have resulted from some breach of the law which Richardson had been called upon to enforce. Steed would also have to give security for Gillett’s other debts “during his lifetime”. What consideration he received for this rather hazardous responsibility is not recorded. But by 1650, when the lease was renewed, Gillett was no longer there. In 1658, John Steed having died, his widow Elizabeth took over Gilletts’s lease, while the larger tenement at 28s passed to Samuel Pleydell, a prominent citizen who was a member of the Corporation.[5] Samuel Pleydell died in 1662, but the hearth tax lists in the following year show Mistress Pleydell paying on six chimneys.[6] Samuel’s son Harim Pleydell took over, and by the time he died at a ripe age, in 1738, he had the entire property which would seem to have been the centre of his grocery business.[7]

Harim’s children all moved away from Abingdon, and by 1753 the grocery business was in the hands of George Knapp, who seems to have obtained the leases as part of a marriage settlement. The part of the property that had been leased at 20s disappears from the records at about this time. It was probably this that was sold off to become the Unicorn Inn, which is known to have existed by 1761.[8] The Knapp family would become wealthy and prominent in Abingdon affairs. George Knapp’s son, also George, was in occupation by 1800 when he took over the lease. Since he was Mayor of Abingdon at the time, the document was signed by the entire corporation.[9] The younger George Knapp became Abingdon’s MP in 1807, but died in 1809.[10]

Finally, in 1811, the two remaining leases were reunited into a single one at 42s, held by Henry Knapp, as heir to George. Henry was a banker. The documents state that the Corner House and its outbuildings and the other messuage connected with it had lately been rebuilt and united, and that the latter “is partly used by Messrs Knapp, Tomkins and Goodall as a banking shop”. It was never the main office of the Knapp bank which was on the High Street.[11]

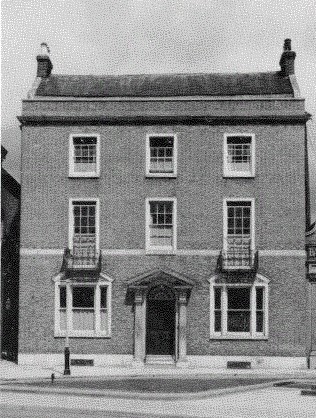

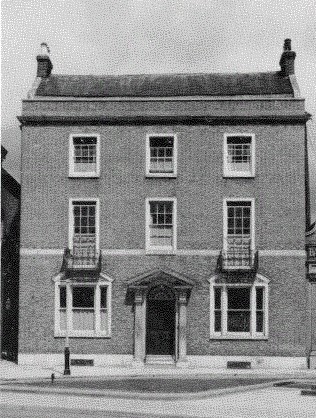

2 The Square, about 1960. Note the nineteenth century lowering of the first floor window cills and the inserted balconies.

(© With thanks to the Berkshire Archaeological Society: P S Spokes, ‘Some Notes on the Domestic Architecture of Abingdon’, Berkshire Archaeological Journal, vol. 58 (1960), pp. 1-19, Plate IX(b))

The handsome new building was in a fashionable style, brick built with glazed headers in toning shades. It has a mansard roof with a front parapet. Apart from some nineteenth century changes to the fenestration it remains as the current Barclays Bank. But in spite of statements in the lease the property as a whole had not been fully unified. There continued to be two sets of premises on the site, now separately occupied, in addition to the inn. For much of the nineteenth century, it is not totally clear which resident holds the future bank. By the time of the 1831 census, one part was occupied by the butchery business of John Vindin Collingwood, a prominent citizen who was mayor at the time. There was a slaughterhouse behind it. The other part was occupied by George Luff, described as a schoolmaster. His household was of twelve people, presumably including boarding pupils. The Unicorn had become the Rising Sun Inn, owned by J.F. Spenlove and managed by John Smith.[12] Smith also had pens where sheep were sold, no doubt replacing the old market in front of the houses.[13] By 1841, the publican was named as James Richards. By 1874, the Rising Sun and the pens had been acquired by the Abbey Brewery, owned by the Morland family.[14]

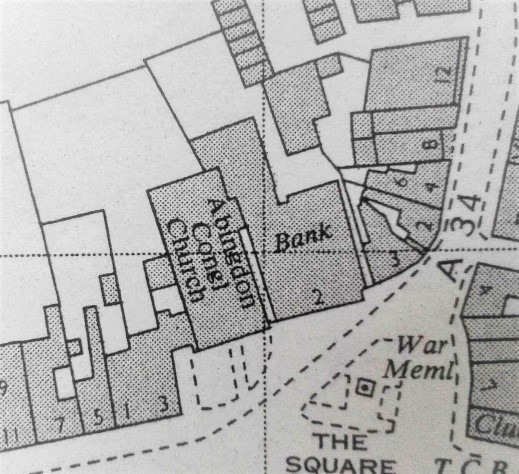

The Square, formerly the Sheep Market – property boundaries in 1844.

The corner plot has been shaded grey and outlined in red. The Rising Sun Inn was in the eastern corner, the Knapp holdings to the west and north. The absence of colour wash shows that the ground is not owned by either the Council or Christ’s Hospital.

Detail from a tracing of a Christ’s Hospital map, by kind permission of the Abingdon County Hall Museum.

Benjamin Read’s survey of 1838 and the map produced for Christ’s Hospital in 1844 compound the uncertainty over the “uniting” of the plot that was referred to in the 1811 lease renewal. The map does show the plot as a single space, but the survey has it still divided into two, with separate, and vastly increased, estimated rental values. A “house and stabling” was occupied by an otherwise unknown Peter Playfair. It had a rateable value of £30 and an estimated gross rental of £46 8s. The other building was Collingwood’s business premises comprising “house, garden, yard, stables, lofts etc”. The rateable value was £38 and the rental estimate £59 9s. The map makes it clear that the freehold was no longer held by the Corporation, but who had acquired it is unknown. At the time of the 1841 census, what had been Playfair’s house seems to have been vacant.[15]

In 1851, the butchery business seems to have been run by John Clarke, while a surgeon, Daniel Stone, had the other house. Another medical man, Henry Edward Dier, seems to have taken over from him by 1881.[16]

In 1871 the resident in what was almost certainly the future bank building was Seth Lewis, a Baptist minister.[17] It is not clear where he officiated; he seems to have been an ordinary member at the Baptist chapel in Ock Street.[18] Aged 58 but having married late in life, he had two small children. The house seems to have been run as a girls’ school. There were two young girls as boarders; Lewis’s wife and sister, and another woman, were recorded as governesses. Unfortunately, Mrs Lewis died in 1877, and her husband moved to Drayton to become minister of the Baptist chapel there.[19] At some time before February 1879 the building returned to its earlier function as a bank.[20]

Gillett’s Bank, Quaker-owned and based in Banbury, had been expanding and had opened in Oxford in 1877. Their first manager in Abingdon was a Captain Ogle, who was soon reported to have resigned to take up a commission in the army of the Sultan of Zanzibar.[21] By 1883 the resident manager was Charles Arthur Bacon, and in 1899 it was Frederick George Sheldon.[22] Gillett’s would become a part of Barclays Bank in 1919.[23]

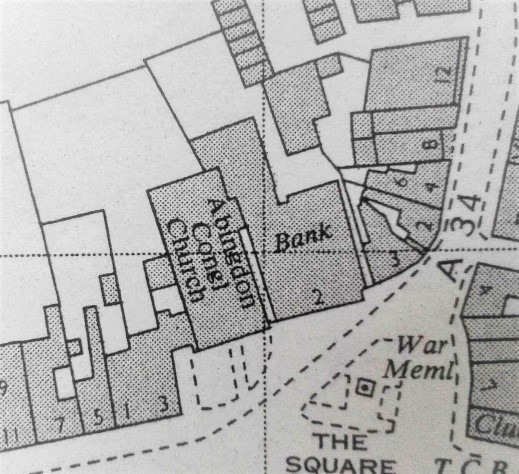

The Square – property boundaries in 1967. Compare the 1844 map.

©Crown Copyright. Reproduced by permission of the Ordnance Survey®

By the end of the century, the Rising Sun inn, which had become a temperance hotel, had been bought by Gillett’s, returning the plot to its boundaries of about 1600. But in further changes it was divided into two, and the eastern portion joined up northwards further into Bath Street. The southern boundary was set back so that the bank building now fronts directly on to the street. The Rising Sun was demolished and replaced by part of the present gabled corner building, designed by JGT West, and the linking small side extension to the bank, very probably also by West. The gabled building is partly in The Square and partly round the corner where it takes in the present 2 and 4 Bath Street. It is a fit successor to Thomas Meadowe’s house “jacens in angulo” of 1554.

See Glossary for explanations of technical terms

© AAAHS and contributors 2018

[1] Bromley Challenor, Selections from the Records of the Borough of Abingdon, 1555-1897 (Abingdon, 1898), p. 32.

[2] Berks Record Office, D/EP 7/83

[3] Corporation Minutes Vol 1, f.89

[4] Unpublished transcripts by J. McGovern from Corporation leases now lost.

[5] Corporation Minutes Vol 1, fols 60, 176, 184.

[6] National Archives, E 179/243/24 (transcript at Berks R.O.).

[7] In naming his son, Samuel Pleydell was showing off his biblical erudition. See Ezra 2:32,39; 10:21,31; Nehemiah 7:35,42; 12:15.

[8] Jacqueline Smith and John Carter, Inns and Alehouses of Abingdon, 1550-1978 (Abingdon,1989), p. 51

[9] Corporation Minutes Vol 4, p. 525

[10] James Townsend (ed), News of a Country Town, being extracts from “Jackson’s Oxford Journal” relating to Abingdon 1753-1835 (1914), p. 124.

[11] Townsend, News, p. 124. Corporation leases are in boxes held by the Abingdon Town Council, which at the time of writing (2018) are on temporary deposit at the Berks Record Office in Reading.

[12] Pigot’s Directory, 1830; Census 1841

[13] Challenor, Selections, p. 340.

[14] It is on the Abbey Brewery schedule of properties.

[15] Read’s survey, 1838, Berks Record Office, D/EP 7/163

[17] PO Directory 1864; 1871 census.

[18] Michael Hambleton, A Sweet and Hopeful People (2nd edn, Abingdon, 2011), pp.132, 135

[20] Berks Chronicle 15 Feb 1879, p. 6.

[21] Oxford Journal 7 August 1880, p.7