The Peyman family – stonemasons and builders

19th & early 20th centuries

Biography

The Peyman family lived in Abingdon throughout the nineteenth century and were an established family of stonemasons, builders, carpenters and related trades. The earliest mention of the Peymans in Abingdon is the baptism in 1781 at St Helen’s Church of Sarah, daughter of Thomas and Elizabeth Peyman.

Thomas Peyman the elder (1750-1835) founded the family firm in 1775. A year later he married Elizabeth Mason at Marcham, moving to Abingdon shortly afterwards. They had seven children, one son who died young and six daughters who survived to adulthood. Shortly after the birth of the sixth daughter in 1789, Elizabeth died and was returned to Marcham for burial. Thomas re‑married in 1790, in Oxford, to Elizabeth Toms (1763-1844). They went on to have five sons and possibly three daughters at their home in Abingdon. Thomas had taken a lease on a property owned by Abingdon Town Council in Bath Street (formerly Boar Street), near to the corner with Broad Street.

A postcard of Bath Street (formerly Boar Street) showing the building at the top end of the street where Peymans lived, to the left of the two white pointed gables. The buildings between Little Bury Lane and Broad Street were demolished in the 1960s to make way for a modern shopping area.

(© From the author’s private collection.)

In 1798 Thomas re-built the old Almshouses-over-the-Water which were situated on the narrow strip of land between the river and the road, opposite Brick Alley Almshouses.

The Almshouses-over-the-Water built by Thomas Peyman in about 1798 are the building with the four chimneys to the right in this view. They and the buildings to their left along the river edge were demolished 1884 when the wharf was redeveloped to create an open riverside area.

(© From a privately-owned postcard. Scan kindly provided by the owner.)

Thomas died 11 December 1835 at the grand age of 85 and was buried in St. Helen’s Churchyard. His wife Elizabeth (1763-1844), their son Thomas (1790-1859) and his wife Sarah (1792-1848) were all interred in the same grave with a headstone marking the spot.

An obituary appeared in the Jackson’s Oxford Journal not only informing the reader of the death but also that Thomas’ father was born in the year 1670. He had “married when he was 80 years of age and Mr. T. Peyman was the issue of that marriage”.

The two eldest sons, Thomas Peyman junior (1790-1859) and William Peyman (1792-1821) would have been apprenticed at an early age into the trades of the family stonemason’s business and they worked together for several years until the untimely and tragic death of William at the age of 29. The tragedy – was it accidental or was it murder? – was painstakingly reported in the Jackson’s Oxford Journal at regular intervals in 1821. In short:

William was found one morning lying on the road near Kennington Common, opposite the paper works, he was unconscious and had a severe cut to the back of his head. His horse was close by. His father, Thomas the elder, was sent for only to discover that William’s pocket book containing about £12 was gone, so were his watch and carpenter’s rule. Sadly William died without re-gaining consciousness. It was unclear as to whether he had fallen from his horse accidentally and then been robbed or was knocked off deliberately and brutally beaten by the villains who had robbed him. On the evidence put before the jury at the Coroner’s court, a verdict of accidental death was recorded. However, there was further evidence that emerged which indicated William had been “murdered” as well as robbed! But this could not be proved. Two men were held in custody for stealing the watch and carpenter’s rule. They were later transported for seven years for “robbing William Peyman whilst lying on the Abingdon Road near Hinksey”. The Coroner’s verdict of accidental death still stood.

Thomas Peyman junior continued to live in the family home in Bath Street and, on his father’s death, became head of the household and continued to run the family business. The Overseers and Churchwardens Accounts at St. Nicholas Church record several entries of payments to the Peyman family for work carried out on the church.

Thomas was married at St Helen’s Church in 1812 to Sarah Prince, also known as Sarah Bartlett (1792-1848). They had ten children. As mentioned above, Thomas and Sarah are buried in St Helen’s Churchyard.

Henry Prince Peyman (1814 – 1877) was the eldest son of Thomas junior and his wife Sarah. Born and baptised in Abingdon, Henry grew up learning the family trade and eventually became a master mason, skilled ornamental sculptor and builder in his own right. Having succeeded his father and grandfather he continued to run the family business from his premises at 24 Ock Street in the former stable range of the Clock House, at one time employing fifteen men and one boy.

The headstone in St Helen’s churchyard to Thomas and his wife Elizabeth, and to their son Thomas and his wife Sarah.

(© Sue Peyman-Stroud)

The font in St Helen’s Church. It was carved by HP Peyman

(© Sue Peyman-Stroud)

However, the most exquisite example of Henry’s work is the intricately carved marble font in St Helen’s Church, signed on the plinth “H.P. Peyman – Abingdon”. This font is a marble copy of the old stone Norman font at nearby Sutton Courtney and it was exhibited at the Great Exhibition of 1851 held in the Crystal Palace at Hyde Park, London.

Following major restoration work on St Helen’s Church in 1872-3, the Churchwarden’s Accounts show an entry where Henry was paid £3. 8s. 0d for “fixing the decorations in the Town Hall at the re-opening of St. Helen’s Church”. It is possible that Henry was involved with the restoration of the monuments at this time and that his font was installed in its current position.

Henry lived with his wife Clara (née Holloway) (1814-1888) and his younger sister Thirza Peyman (1836-1911) who was twenty-two years his junior. The family business operated for over fifty years from 24 Ock Street, which is part of the Clock House complex of buildings. It was also at these premises that the Mechanics’ Institute had their library and reading room for over 20 years. The Institute had been established in 1854 with the aim of spreading “useful knowledge” and to “elevate the mind and bring the different classes of the town into social intercourse with each other.” Henry was appointed Treasurer. It moved to the Clock House in 1857 – the Institute’s rooms were situated above the carriage arch and below the clock tower – and the day-to-day supervision of the library and newsroom was carried out by Clara and Thirza.

Henry met an untimely and sudden death in 1877 when he had a seizure whilst visiting the offices of Mr. Morland in Bath Street, from which he never recovered, much to the grief of all who knew him. Clara and Thirza probably struggled to continue running the business efficiently as well as the Mechanics’ Institute reading room and may have been relieved when the Institute closed its doors for the last time in 1879 due to a fall in support and competition from other organisations.

The same year that the Mechanics’ Institute closed, 1879, there was a disastrous fire on the opposite side of Ock Street which started in a furniture warehouse and soon spread to adjacent premises. The fire brigades from Abingdon and Culham endeavoured to control the fire by pumping gallons of water onto the flames. Many people came to assist in salvaging as much property as possible from the nearby dwellings and shops. Clara and her neighbour at Clock House Mr Paulin Martin, a surgeon from Highworth, Wiltshire, made available their rear premises for the storage of the rescued goods. Mr. Martin’s coachman acted as security guard to protect the items in Clara’s back yard.

In 1881 the Beaconsfield Working Men’s Conservative Club opened in Ock Street in “premises formerly in the occupation of Mr Peyman, stonemason”. The building had undergone various alterations to create a large upper room with a committee room and lobby underneath at street level. This arrangement would have left some ground floor space where the stonemason’s business could continue.

Detail from a postcard of about 1900 showing “T. Peyman – Abingdon Monumental Works” in the white “Z” banner on the side of the former stable building at the Clock House. The main house of the Clock House complex is on the right.

(© From the author’s private collection)

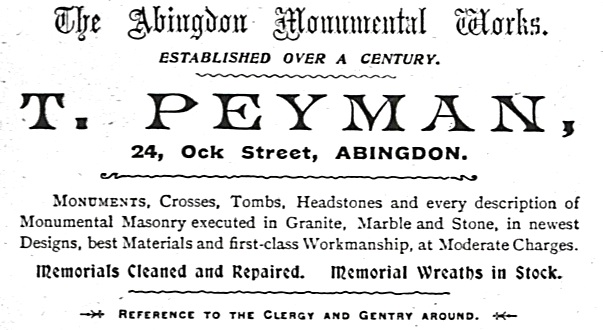

On Clara’s death in 1888 Thirza Peyman took over the business as “Manageress” employing two men. She had her name painted on the side of the building: “T.Peyman, The Abingdon Monumental Works”.

She also advertised in Hooke’s Abingdon Almanack and Directory in 1903, 1904 and 1905. The business may have been sold shortly after this last date.

Thirza Peyman’s advertisement in Hooke’s Abingdon Almanack and Directory 1904

(© With thanks to Abingdon Library)

Thirza moved to 24 Radley Road, Abingdon. When she died, at this address, in 1911 she brought to an end the Peyman era in Abingdon which had lasted for over 100 years. Henry, Clara and Thirza are buried together in the churchyard at Shippon under an unusual and very unimposing memorial stone.

The memorial in Shippon Churchyard to Henry Prince Peyman 1814-1877 his beloved wife Clara Peyman 1814-1888 and his sister Thirza Peyman 1834-1911

(© Sue Peyman-Stroud)

Thirza never married so the main beneficiaries of her will were Mary and Dorothy Martin, daughters of Dr Paulin Martin of 26 Ock Street and her good neighbours for many years. They were also appointed to execute her will.

Other Peymans who had been born in Abingdon ventured elsewhere in search of work and adventure, to places such as Oxford, London, Birmingham, Kent and as far away as Australia and New Zealand. Many of them took with them the Peyman trades of stonemason/builder/carpenter and painter which, in some cases, still continue to this day.

Sue Peyman-Stroud

© AAAHS and contributors 2019