Figure 1Tomkins Almshouses, internal courtyard

© D Clark

Located at the junction of Ock Street and Conduit Road, the Tomkins Almshouses (Fig.1) are not only an attractive group of dwellings but are also unusual in Abingdon in making a strong architectural statement. At the far end is a classically-inspired frontispiece with a shaped gable and semi-circular arched doorway with a keystone. Above is a panel commemorating the donor, Benjamin Tomkins, who in 1732 left £1600 in his will as the endowment for the almshouses for ‘four Poor Men and four Poor Women for Ever’. Apart from some necessary modernisation, the Tomkins almshouses are almost exactly as they were built in 1733.

Tomkins (Fig.2) was a rich maltster in Abingdon and one of his properties in Ock Street comprised a house, malthouse and granary. He left strict instructions to his sons, Benjamin and Joseph, for the erection of the almshouses on this site, including a pump and a ‘necessary house’ (toilet). The building we see today shows that his wishes were carried out to the letter.[1] The courtyard layout was Tomkins’ idea, and the builders were probably the local men Samuel Westbrook and Charles Etty, who had worked for Tomkins on one of his houses, Stratton House.[2]

Benjamin Tomkins’ will required the almsfolk to come from the parishes of St Helen’s and St Nicolas, or others within four miles of Abingdon,[3] but although he was a staunch Baptist, Tomkins did not insist that they were also of that persuasion.

In 1751, Benjamin Tomkins’ grandson, another Benjamin, who had inherited the responsibilities of an almshouse trustee, continued his grandfather’s legacy of micromanaging the activities of his heirs by requiring that ‘the men and women’s clothes be of a light Brown colour, cuffed with White plush, exactly to match the patterns herein left’. He also specified that they should have new gowns every year.[4]

Benjamin senior had provided £1600 to be used for the purchase of lands that could provide sufficient rental income to pay for the support and maintenance of the residents, to be paid to them weekly. The property investment of the Almshouse Trust was a farm of 73 acres at Weald, near Bampton, the rest was invested in Gilts.[5] In 1907 these were providing sufficient funds for payments to the almsfolk of six shillings a week in winter and five shillings in summer, an annual total of £103 8s 6d.[6] There is no mention of new gowns. The almoner (Mr George Staniland) was paid an annual salary of ten pounds. Lesser sums were spent on rates and insurance, repairs and chimney-sweeping for the almshouses, but the farm at Weald also needed maintenance and £5 16s 6d was spent on thatching the barn. The farm was sold in 1919.

Figure 2 Benjamin Tomkins (c.1663-1732) showing off his wealth

(Artist unknown. Courtesy of the Abingdon Town Council)

The almshouses were conveyed to Christ’s Hospital in 1987.[7]

The accommodation was arranged in two rows facing each other across a courtyard (Fig.3), and each resident had two rooms, each 12ft square. Although from the street they appear to be two-storied, the upper windows in the gable ends are blind. Although there are now slight differences between the units, their basic layout is the same – a central doorway opens into the living room, which had a corner fireplace with a salt cupboard at each side. The other room was the bedroom. The facilities were modernised in the 1950s with the inclusion of kitchen units in the living room and a toilet and shower room in the bedroom, retaining the salt cupboards with their original doors and hinges. New windows were set into the walls – including those to the Conduit Road elevation, which in 1733 was a blank wall alongside a gateway to the fields behind. In 2002 there were further rearrangements and upgradings (Fig.4).[8]

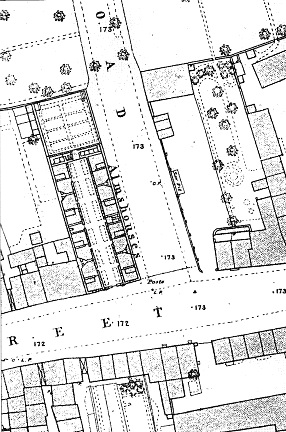

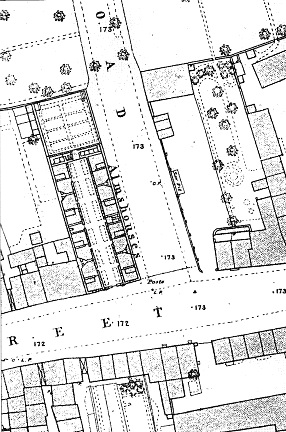

Figure 3 Extract from 1st edition OS map at 1:500 (With thanks to Oxfordshire Library Services)

Figure 4 A typical almshouse living room

© D Clark 2018

The façade to Ock Street (Fig.5) makes an architectural statement: it consists of two shaped gables in glazed bricks, laid in header bond. The cross-mullioned windows to the ground floor rooms have segmental heads with stone keys standing proud of the surrounding brickwork. Between the gables are two brick piers topped by stone finials. The soft red bricks are laid in English bond with fine white mortar joints. The piers support iron railings and gates. Each brick pier is topped by a decorative finial.

Figure 5 Tomkins Almshouses

© D Clark 2018

The west wall (visible from Crown Mews) is rubble stone, while the east wall (to Conduit Road) is Flemish bond brickwork. Set in the latter is the Carswell (or Mr Ely’s fountain) of 1719 (Fig.6), part of the town’s water supply until 1874 but located in Ock Street on the other side of the almshouses until it was moved here in 1947.[9]

Figure 6 The Carswell

(© D Clark)

The central courtyard is strictly symmetrical and each side has a crenellated centrepiece – one of these supports a modern lamp fitting – with a taller doorway than those to the individual units. These led to the pump and the toilet. The brickwork is again largely of glazed headers, but the individual doorcases are in stone. The cross-windows to the rooms are similar to those facing Ock Street, but have opening casements with leaded glass and their original catches, handles and quadrant stays.

The centrepiece is a ‘gatehouse’ and supports a weathervane bearing Tomkins’ initials and the date of 1733, but the clock above the commemorative panel was installed within a blocked lunette in 1990, replacing the earlier turret clock.[10] The door seems somewhat incongruous, and when first built the archway was probably open, framing the garden beyond, shown in nineteenth-century maps (Fig.3) as having a layout of rectangular plots with paths between. Tomkins’ will specified that each resident should have a plot – presumably to grow vegetables – but over the years it has become a communal area for rest and relaxation.

Figure 7 The bell purporting to be from Tomkins Almshouses

© D Clark 2018

A bell in Abingdon County Hall Museum (Fig.7) has a plaque dated 1910 stating that it came from the almshouses, though the information it gives about Benjamin Tomkins is wrong. The plaque bears the name of Harding Herbert Tomkins, probably a descendant.[11] The bell has recently been identified as having been cast by Edward Hemins of Bicester.[12] It bears the date of 1733 and has the name ‘James Crouchfeild’ cast into it. In 1971 it turned up in a scrap dealer’s yard and was acquired by the Town Council for £110. It has been on display in the County Hall Museum since then.

There are some difficulties with this story, however. The misleading inscription does not instil confidence, and indeed why would a bell have been needed anyway, as there seems to have been a clock at least since 1737. In that year there was a payment in the accounts – now at Christ’s Hospital – for ‘Oyle for ye Clock and cleaning Chimneys’. Later there are payments to a James Crutchfield between 1740/1 and 1757 for ‘cleaning ye clock’, so this seems to link the bell with the almshouses – but the bell does not show evidence of having been struck repeatedly by a clock-driven hammer, and indeed it has a clapper which would not work with the clock – though the clapper may be a later addition. And why would someone being paid to clean the clock have his name cast into a bell – surely the sign of a person of some importance?

It would be interesting to know who designed the almshouses. From Tomkins’ will the description of what he wanted – and the measurements given there of the rooms and ranges – it is clear that the idea of the narrow courtyard plan is his. But was Tomkins aware of an example of this plan as a possible way of using the space? Most examples are some distance from Abingdon, for example in some early foundations such as Ford’s Hospital in Coventry (around 1509) and the Trinity Almshouses in Salisbury (founded 1379 but rebuilt in 1702). Many of the other examples have larger courtyards such as the Sir John Port almshouse in Etwall (Derbys.) of 1681/90, with two-storey cottages and the Trinity Green almshouses in Mile End Road, Spitalfields, London, of 1695. A nearly contemporary example to Tomkins’ is Winsley’s almshouse in Colchester, founded in 1728. This has a similar mannerist frontispiece but the courtyard is much wider and the houses much larger. Perhaps the closest analogy is Penny’s Almshouse of 1720 in Lancaster. It has a central chapel behind a shaped gable, but the five units in each of the wings anticipate the enclosed aspect of Tomkins’ almshouses. There is also an example in Haarlem, Holland but again this is on a grander scale than that in Abingdon. The obvious model is the local example at Lyford, though in its present form it is a rebuilding in the later eighteenth century – but which may have retained the layout of the building that was there in the 1730s.

It is obvious that the almshouses were intended to make a statement, part of which was to perpetuate the name of Tomkins as one worthy of respect in Abingdon. But there was an unusually large population of Dissenters in the town, with Benjamin Tomkins effectively their head, and who were contributing massively through local taxes to town charities but were largely excluded from their benefits as the borough corporation was run by the Tory/Anglican elite. These men – in their alter ego of Christ’s Hospital – had recently built the prestigious Brick Alley almshouses using funds from a sixteenth-century grant which they were also milking unashamedly. The Dissenters must have felt a need to prove that they too could look after their own in a no less opulent style but without the moral ambiguity.

The shaped gables are typical of what John Summerson calls ‘artisan mannerism’ and the battlemented centrepieces are an early example of the ‘castle style’ strand in the story of the continued use of Gothic features in secular buildings in England throughout the eighteenth century. The frontispiece at the end of the courtyard is in red brick, but set in a wall of glazed headers. The concept is almost that of a triumphal arch, a brick version of the gate of Virtue at Gonville and Caius college, Cambridge, built in 1567. The likely meaning, therefore, is that Tomkins has been commemorated as what we might now call a Renaissance or Enlightenment man, with taste, but also successful and triumphant in life, yet seeking to establish his personal legacy ‘for Ever’ by his endowment, and so through this building, triumphant also in death.

But these details are not specified in Tomkins’ will, so who was responsible for them? If it was Samuel Westbrook himself, perhaps he ought to be recognised as more than ‘just’ a builder. We know he worked on other houses in Abingdon, such as the Clock House and Stratton House, but at the Council Offices of 1731 where he also worked, he was supervised by the architect John Stevens of Wantage, though sadly this is the only building with which Stevens is known to have been associated.[13] Perhaps Westbrook did not need any ‘supervision’.

The buildings have not changed much since 1733. The door to the garden may have been inserted slightly later, and wash-houses were added behind the accommodation ranges in the second half of the nineteenth century. In the 1950s, with the creation of ensuite facilities the central alcoves were remodelled as part of the living accommodation of the adjacent units. Since then, gradual updating has taken place as necessary.

We know the names of the residents and something of the arrangements there from the available censuses (Fig.8). For example in 1901 three of the residents had other family members staying with them on census night: Ellen, Joseph Argyle’s niece, aged 47, Margaret, James Winter’s 59-year old needlewoman daughter, and Gertrude, Harriet Edgington’s 13-year old granddaughter, an apprentice dressmaker. While it is possible that these were just casual visitors, one cannot help wondering whether one or more were semi-permanent residents, somehow sharing the accommodation, perhaps acting as carers for their relatives. Later in the century it seems that couples were living there together. Some residents lived in the almshouses for considerable periods of time – in a few cases twenty years or more.

Life in the almshouses has in some ways changed dramatically since 1733, with modern facilities and heating supplied from a central boiler. The numbers of men and women vary from the specified four of each, and they do not wear identical gowns. Yet if Benjamin Tomkins were to return today he would recognise many features of his foundation. There are still strict rules of conduct, and expulsion is not unknown. The residents are largely self-sufficient, though some require outside help with cleaning, and the garden is not used for growing vegetables. They share tasks and are very much a community – ‘we all get on very well and have fun too’, said one of them.[14]

Figure 8 The residents in the courtyard of Tomkins Almshouses in the early twentieth century

(© Gail Durbin and reproduced by kind permission, 2018)

© AAAHS and contributors, 2019

[1] The National Archives (TNA) ref. PROB 11/658/207

[2] Agnes Baker (1963) Historic Abingdon (Fifty-six Articles). Abingdon. p.31

[3] Cox (1999) p.63-4 quoting TNA PROB 11/658/207

[4] recited in the Statement of Accounts of the Tomkins and Buswell Charities for the year ended 31 December 1907 (Angus Library D/TMK2)

[5] Angus Library D/TMK2 Statement of Accounts of the Tomkins and Buswell Charities for the year ended 31 December 1907

[6] Angus Library D/TMK2 also has a ledger entitled ‘Almsfolk Pay’ with sums disbursed from 1907

[7] Christ’s Hospital leaflet (anon; n.d)

[8] Vale of White Horse planning reference 02/00721/LBC

[10] Vale of White Horse planning reference P90/V1035/LB; list description.

[11] There was a Harding Henbest Tomkins living around this time, who may – or may not – be the same person

[12] by Chris Pickford (pers. comm.)

[13] Colvin, Howard (2008) A Biographical Dictionary of British Architects1600-1840, p.985

[14] information in this paragraph from Adrienne Compton-James (pers. comm.) and Hasnip, Audrey (ed) (2006) Cameos of Abingdon Abingdon. p.42