Caldecott House (demolished 1972, was on Caldecott Road)

Caldecott House was on the north side of Caldecott Road and at the time of its demolition in 1972 was one of the largest houses in Abingdon (Fig. 1). But very little is known about its builders, and no formal record of it was made before or during its demolition. Yet is has been possible to put together a plausible history, from maps and documentary evidence. In particular a map commissioned by its owner in 1762 (Fig. 2) has been particularly useful in understanding not only what the house looked like at that time, but also the nature of the landscaped garden in which it stood.

Figure 2.

1762 estate map – north to right.

(© Abingdon County Hall Museum, accession number ti 1633.67.15)

It seems that the earliest part – to the left in Figure1 and a red square on the map – was built in 1738 as a datestone was recorded there and so the likely builder was John Saxton who was leasing the property from Christ’s Hospital at that time. It lay behind an earlier farmhouse, which was demolished by William Birch in the 1760s when he extended the house to the north. The palatial pile to the right of Figure 1, dwarfing Saxton’s house beside, was probably built by the Lintells, who bought Caldecott in 1829. The final gentrification to create a symmetrical east front carried out by Major-General Bailie in the 1890s.

Too big for a family home in the 1930s, it had a short period as an hotel but was requisitioned in 1940 by the Air Ministry for Bomber Command Accounts staff. From 1945 Caldecott House was a Dr Barnardo’s home until it closed on 31 August 1971. It was demolished the following year and there is now a housing estate on the former grounds. The only structures to survive are the lodge of 1870 on Caldecott Road and a stone archway from the Bailies’ garden.

A significant feature of the earlier garden was a double-moated feature called the Wilderness, which survives in part, though it is not easily datable – it could have medieval origins, though more likely was created as an orchard in the seventeenth century.

© AAAHS and contributors 2021

Caldecott House was on the north side of Caldecott Road and at the time of its demolition in 1972 was one of the largest houses in Abingdon (Fig.1). But very little is known about its builders, and no formal record of it was made before or during its demolition. More is known about its owners because they were rather well-off people, whose wills were proved at the Prerogative Court of Canterbury and are available online at the National Archives. One of these owners commissioned a map of the estate in 1762, and this has proved invaluable in understanding not only what the house looked like at that time, but also the nature of the landscaped garden in which it stood.

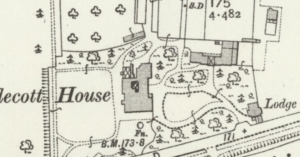

Before the borough boundary of Abingdon was extended southwards in 1870, the Caldecott estate was in the parish of Sutton Courtenay. It consisted of some 23 acres between the river Ock to the north and what is now Caldecott Road to the south (Fig.2). The boundary to the west was a common field of the hamlet of Sutton Wick. To the east was the Mill orchard, owned by Christ’s Hospital, and the boundary was a ditch running due south from the Ock to Caldecott Road, parts of which survive today along the roadside and within the housing estate at Manor Court.

Figure 2. Caldecott House and garden in 1912. Extract from 1:2500 Ordnance Survey map.

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.)

The lodge on Caldecott Road at the entry to St Amand Drive (Fig. 3) is now the only surviving building. It was built by John Hyde in 1870 as can be seen in the date-stone (Fig. 4). From it, the visitor in the late nineteenth century entered the estate through woodland to an open area, around which were various buildings – the house to the west and a stable and coach-house block to the north. In the centre was a fountain. Beyond the house to the west was an open park, protected by an embankment of some sort from the area beyond. North of the woodland was a formal rectangular kitchen garden, with some trees and greenhouses along the northern edge, while in the centre was a sundial. The rest of the park seems to have been grassland with scattered trees.

Figure 3. Caldecott House lodge

(© D Clark, 2021)

Figure 4. Datestone J H 1870

(© D Clark, 2021)

Adjacent to the southern stream of the Ock to the north-west of the house was a double-moated garden feature – later called The Wilderness (Figs.5 and 6). By 1877 it had two bridges, one in a Japanese style, to the wooded central island, which had a circular feature in its centre.

Figure 5. The Wilderness from the west (© D Clark, 2021)

Figure 6. The Wilderness (1762)

(© Abingdon County Hall Museum, accession number ti 1633.67.15)

The origin of the Wilderness is another of the questions relating to Caldecott that we have not yet been able to answer. It could be medieval (like Henry V’s Pleasaunce at Kenilworth), late sixteenth-century (like Sir Thomas Tresham’s moated orchard at Lyveden New Bield), or early seventeenth-century like the orchards promoted by William Lawson in his 1618 book on gardening.[1] All we know is that it was there by 1762 when it was called ‘the old orchard’.

Owners and occupiers

The early history of the manor of Caldecott was recorded by the Victoria County History, but little seems to be known about a house there, apart from a report that in 1479 it was recorded that the original site of the manor was lost, implying that there was a medieval manor house somewhere.[2] There is also a possibility that Caldecott was the area described as occenes gaerstun (grass enclosure by the Ock) in a charter dating to 956, which describes the boundary of an area somewhat similar to the later parish of St Helen Without.[3]

The earliest recorded lords of the manor were the de Turbervilles, one of whom granted it in 1291 to Abingdon Abbey.[4] After the Dissolution the estate was leased to William Bysley, and in 1553 to Edmund Cowper, clerk, and Valentine Fayrewether, haberdasher of London. By 1565 Richard Smith was the leaseholder and on his death it passed to his son Richard who was succeeded in 1583 by another Richard.[5] One of these had a son, Thomas, described as a ‘gentleman, farmer of Caldecott’ and who was also a burgess of Abingdon and served as mayor in 1583-4; his wife was Joan Jennings and Sir Thomas Smith (c.1556-1609) was their son.[6] Thomas died in 1597, and the family connection with Caldecott ended.

The VCH then goes on to record that ‘Charles Tooker of Abingdon was in possession of the site of the manor in 1617 and died seised in 1626 when he bequeathed it to Charles, his younger son.’[7] There is then another gap in the record until 1741, which is unfortunate as there was once a datestone of 1738 on part of the house – the three-bay block to the left in Figure 1.

Somewhere in this gap we encounter the Saxton family whose name is commemorated in nearby Saxton Road. Clement Saxton was thrice mayor of Abingdon and died in 1730, leaving an estate at Goosey to his son Edward, and estates in Sutton Wick – presumably including Caldecott – to another son, John. While John is the most likely builder of the first Caldecott House, another candidate is William Birch, to whom the Christ’s Hospital lease had been reassigned by 1741. Birch died in 1751 and bequeathed his real estate ‘in Sutton Wick and Abingdon’ and his ‘leasehold estate held under the Hospital’ to his nephew, another William Birch, a businessman and philanthropist.[8] At this time William was living inLondon, and Caldecott was let to a series of tenants including the Revd Thomas Carte, who died there in April 1754 while working on his History of England.[9] However in 1756 Birch renewed the Christ’s Hospital lease for another 21 years. He became a trustee of Thomas Coram’s Foundling Hospital in 1760 and around that time came to live in Caldecott. As was often the case with hospital governors, his wife Sally supported him in this role – she was an inspector for the wet-nurses employed by the Foundling Hospital in North Berkshire.[10] In October 1762, however, family circumstances caused Mrs Birch to move back to London, where they were living in 1770 when William renewed the lease again. William died in 1800, his wife in 1803.[11] The Birches seem to have purchased the freehold of Caldecott at some point before 1804, as the eight parcels making up the estate are so designated – with ‘Sarah Birch’ as the proprietor – on the Sutton Wick Enclosure map of 1804.[12] The map also shows that by then there were a number of extensions to the square structure of 1762.

We now return to the Saxtons, as Edward’s eldest son, Clement Saxton (II), born in 1724, seems to have rented Caldecott in 1762 after the Birches left. He was a Captain in the Berkshire Militia in 1762 and a Lieutenant-Colonel from 1776–1787. In between he was appointed High Sheriff of Berkshire (1777). There is no evidence that he lived for any length of time at Caldecott, however – it was certainly rented out in 1796, as we shall see later. He seems to have been confused with his brother Charles, who was thought to have lived at Caldecott in the 1780s, perhaps as a tenant, though as we shall see later, his nephew, another Charles, did inherit the estate.[13] Clement does not seem to have lived up to his name – he had a ‘conspicuous boorishness in manners’. He died in Shippon in 1810 but is buried in St Helen’s. His memorial was ‘placed here by his grateful and affectionate nephew Sir Chas. Saxton second Baronet, 1812’.

The estate (still owned by the Birches) seems to have been rented next to Joseph Tomkins (possibly b.1763, d.1841, and a linen draper, son of the builder of Twickenham House) as there is a letter dated 8 January 1796 addressed to Miss Martha Steele c/o J. Tomkins, Esqr Caldecot House, Abingdon, Berks.[14] Martha was the sister of Mary Steele, (1753-1813) a ‘dissenting writer’ of some renown and half-sister to Anne Tomkins.[15] She often stayed with her brother-in-law, Joseph Tomkins at Caldecott House (Anne Steele married Joseph Tomkins in December 1791). By 1797, however, they seem to have moved to Oakley House at Frilford, as the later Steele/Tomkins correspondence is addressed there.

Another tenant in 1796 appears to have been a Miss Holwell, of whom Jane Austen wrote bizarrely in a letter to her sister Cassandra on 15 September of that year, “Mr. Children’s two sons are both going to be married, John and George. They are to have one wife between them, a Miss Holwell, who belongs to the Black Hole at Calcutta.”[16] This reference links her to John Zephaniah Holwell, a doctor in the East India Company who was one of those imprisoned in the fort at Calcutta and who wrote a controversial account of it later.[17] We have not been able to identify Miss Holwell, but she is likely to be either a sister or niece of William Birch’s wife Sally (1738-1803), who was John Zephaniah Holwell’s eldest daughter.

Clement Saxton II seems to have bought the freehold of Caldecott at some point between 1804 (when owned by Sarah Birch) and 1808 (the date of his will) as he bequeathed to his nephew, Sir Charles’s son, also Charles Saxton (II) his ‘freehold lands in Sutton Wick’ (which may have included Caldecott) though unspecified leases and leaseholds are also mentioned.[18] No wonder Charles was a ‘grateful and affectionate’ nephew.[19]

Sir Charles Saxton (II) continued his association with Caldecott until 1829, when it was offered for sale, as a ‘comfortable mansion house, called Caldecott House, with lawn, pleasure-grounds, and paddocks, in the occupation of Daniel and Thomas Lintalls, Esqrs., together with an excellent farm house and residence, with all necessary agricultural buildings.’[20] The Lintalls who had been renting the house initially comprised Thomas Lintall, his wife Elizabeth, daughter Anne and twin sons Thomas and Daniel. Anne married the local MP Edward Loveden Loveden in 1794, and Elizabeth died in 1820.[21] The twins continued to live there and they bought it at the 1829 sale. The Lintalls are the most likely builders of the massive south range (to the right in Figure 1). Daniel having predeceased him, Thomas Lintall died at Caldecott House on 21 February 1841 aged 71.[22] He bequeathed the house to the Revd John Stonard DD, rector of Aldingham in Lancashire, along with the furniture, plate, linen, books, wine, household implements, harness, horses and the rest…[23] Stonard lost no time in selling Caldecott probably because he needed the money to build a new house, Aldingham Hall. [24] He died in 1849 before it could be completed and bequeathed it to his butler, Edward Schollick. Stonard’s will of 1849 also mentions the linen etc that he inherited.[25]

The myth that Thomas Lintall bequeathed Caldecott to his butler, Thomas Musson, may have arisen partly because of the Stonard bequest, but also because Thomas and his brother William did inherit funds from Lintall, and presumably between them they had enough eventually to acquire the property. A memorial to William Musson (d. 1854) in the churchyard of St Helen’s refers to him as “(Gent) Caldecot House Parish Sutton Wick.”

Whoever bought Caldecott in 1841 seems again to have rented it out. On 18 July, 1847, Richard James Spiers – later to be mayor of Oxford – “rode, after dinner at Milton to have tea with Kate at Caldecot”.[26] Kate was his sister, and widow of Edward Standen, a great friend of Spiers.

Following the death of William Musson, the estate was put up for sale by auction on 4 May 1854. [27] By then it had three principal bedrooms, with dressing rooms, seven secondary bedrooms, dining room, drawing room, breakfast room, two staircases and other offices. The garden is described, and it also refers to a detached cottage. The furniture was sold separately in November.[28] The purchaser in 1854 was a Mr Bartram, who was carrying out repairs in June 1855 when a tit was found to be nesting in a letter-box.[29]

The next newspaper reference is to James B Burke “of Caldecott House”, who in 1857 successfully sought the prosecution of a Mr Lyford of Drayton for “damaging the footpath between Abingdon and Sutton Wick”.[30] Burke seems to be a railway engineer, at one time assistant to Brunel, and who was involved in building the Abingdon Railway.[31] However, he got into financial difficulties, mortgaged the house, and eventually had to sell it. The sale notice refers to the work he had been carrying out to extend the building, though this was unfinished.[32]

It was again offered for sale on 25 August 1857, and on 3 June 1858 the ‘excellent new building materials’ sold, the new (unnamed) owner clearly not wishing to continue the work on Burke’s extension.[33] Although not mentioned in the advertisement it seems that the partly completed work was also demolished, the stones were recovered and were no doubt incorporated in the houses being built in Abingdon at the time.

The purchaser in 1857 was probably John Hyde – he can be found there in the 1861 census. The Hydes were Abingdon clothiers whose house and works were in West St Helen Street from the mid-eighteenth century. John Hyde (b.1798) took over the business from his father (also John Hyde, 1778-1864) in 1833 and expanded it greatly, building a large clothing factory near St Helen’s church in 1852. He was a member of the committee formed to promote the candidacy of Col. The Hon Charles Hugh Lindsay MP in the 1868 Election for the seat of Abingdon, and gave Caldecott as his address. In November 1871 he wrote from Caldecott House to the then Mayor indicating that he would not stand for re-election, after 36 years as an alderman, “old age and infirmity creeping up on me”.[34] He died the following year (8 June 1872).

His brother, Thomas, gave Caldecott House as his address when acting as his executor in the same year. Thomas Hyde spent most of his life as a wholesale clothier in Summertown, Oxford. It seems he returned to Abingdon and Caldecott on his brother’s death and lived at Caldecott until his own death in 1875. He probably supervised the installation of a memorial window to the Hyde family in St Helen’s church, the finance for which came from his brother’s estate.[35]

He was still alive on New Year’s Day, 1875 when he gave a substantial dinner for the almsfolk in the hall at Long Alley.[36] He died on 6 August, leaving an estate of “less than £120,000”.[37] His will was proved on 1 September by his son Thomas Hyde (II) of Caldecott (1854-1908). Mrs Emma Hyde, Thomas’s widow, continued living at Caldecott and died there aged 61 on 10 January 1880.[38] She was certainly well off, as her Will of 27 March 1880 suggests.[39]

Thomas Hyde (II) seems to have been interested in the agricultural side of the estate, as his cattle won prizes at shows. He was reported in the local press as holding a number of events in the gardens at Caldecott, including sports days and in 1881 he hosted a bazaar in the grounds in aid of the North Hagbourne church building fund. Hyde sold off the contents in 1882, for, as the advertisement states, “the owner, T Hyde Esq., who has let the above Residence for a term of years, .. is leaving the neighbourhood.”[40] On February 23, 1884, Mrs E J C Studd gave birth to a daughter at Caldecott House.[41] The Studds were probably renting the house – advertisements in Jackson’s Oxford Journal later in the year show that “T Hyde” was still managing the farm and selling crops and stock.

In 1886 an account in the newspaper refers to “the Revd C. Dent’s grounds in Caldecott”. He also seems to have been doing some ‘hobby farming’ in the late 1880s, but Thomas Hyde was also managing livestock on the estate, until on 22 September 1888 he offered for sale not only livestock but also farming equipment at Caldecott and Sutton Wick farms.

By 1890 the Revd Dent had moved on, and this is probably the year in which Caldecott was bought by Maj. Gen. Thomas Maubourg Bailie and his wife Amy. Bailie was born in Bombay, India, on 16 August 1844, the son of Colonel Thomas Maubourg Bailie (1797-1844).[42]Thomas (II) rose quickly through the ranks – he was a lieutenant in 1865 and a colonel in 1881. However in 1885, while serving in the Oxfordshire Light Infantry, he was placed on temporary half-pay on account of ill-health.[43] A year later, on 26 June 1886 he married Amy Elizabeth, eldest daughter of Sir William Miller, Baronet, of Manderston who had made his money trading hemp and herrings with the Russians.[44] By 1891 they were at Caldecott House, though their eldest son, aged 3 was born in London. Thomas was at this time commanding the 43rdRegimental District, and they had nine servants in the house.[45] They were at Caldecott during the great flood of 1894, as, according to the newspaper, they were “flooded out” and the General and his establishment were “forced to seek refuge in the Vicarage”.[46] On July 1 1899 a son was born to the Bailies at Caldecott, but in 1901 the family were living at 54 Sloane Street in London – with nine servants – and most of their children were born in London. Perhaps Caldecott was their ‘country house’ – or perhaps they feared another flood. The Bailies created a new garden to the south of the house, and one of the stone arches from it survives today within the estate (Fig. 7). This, like ‘Trendell’s Folly’ in the grounds of Old Abbey House, seems to consist largely of recycled medieval stone.

Figure 7. Stone arch in grounds

(© D Clark, 2021)

Major-General Bailie died in London in April 1918, and Amy eventually moved to Wharf House – which the Bailies also owned – with her daughter, Amy Hope Bailie. Mrs Bailie died in London in 1942, and Hope remained at Wharf House until her death in 1969.[47] Major-General Bailie’s son Hugh seems to have been living in Caldecott after his marriage to Nancy Laura Hargreaves Ferrar in 1921 as their son was born there in 1922. Caldecott was offered for sale in 1935, with a photograph showing the house facing a formal lawn, with specimen trees behind (Fig.8).

Figure 8. Caldecott House (east elevation) in 1935

(From the sale catalogue [48] )

In 1938 a Mrs Boyd turned Caldecott into an hotel, but this was short-lived as it was requisitioned in 1940 by the Air Ministry for Bomber Command Accounts staff. They were housed in nine prefabricated bungalows which were erected to the west of the house in the grounds adjacent to Caldecott Road. In 1945 Caldecott House became a Dr Barnardo’s home, at first for boys only, then from 1952 a mixed home until it closed on 31 August 1971. It was demolished in 1972 to make way for the present housing estate.

The house

There appear to be three types of structures shown on the 1762 map (Fig.9). Those in red seem to be dwelling houses, the dark blue ones stables, while those in yellow are probably agricultural buildings of some sort – all are in the “House, Garden, Farm &c” area.

Figure 9. Buildings on 1762 estate map – reoriented with Caldecott Road across the foot

(© Abingdon County Hall Museum, accession number ti 1633.67.15)

There are three red-coloured buildings, two to the east almost conjoined and enclosing a garden, and the third, square, on its own to the west. A barn and the red house opposite across the entrance driveway can also be made out on the 1804 Inclosure map.[50] But other buildings had been demolished and the western building had been extended to the north – so probably by one of the William Birches. By the 1870s, however, the huge (and ugly) south wing shown to the right in Figure 1 had been added – probably by the Lintalls who had to cater for two separate households. This larger house appears on the 1877 OS map, which shows the building enclosing a central courtyard, with a conservatory to the north-east. Figure1 shows this arrangement, with what is probably part of the earlier house between the later wing and the conservatory to the north. The farmhouse remained until the mid nineteenth century.

The plan of the house shown on the 1912 map (Fig.9) shows an alteration – the creation of the symmetrical east elevation shown in Fig.8. The fountain in the forecourt seems to have been replaced by another to the south of the house. The twentieth-century maps show no change of footprint thereafter. Both the Hydes and the Bailies seem to have had the financial resources to make alterations, but the Hydes were all fairly old when they came to Caldecott and do not seem to have needed extra accommodation. The Bailies, on the other hand, had aristocratic links and although they had a town house in London, perhaps they needed a grand show-house in Berkshire.

Figure 10. Caldecott House in 1912

Extract from 1912 Ordnance Survey map.

(Reproduced with the permission of the National Library of Scotland and licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike 4.0 International License.)

This analysis suggests that what seems to have happened is that John Saxton built himself a grander house in 1738 behind the existing farmhouse at Caldecott. Then before the end of the century the Birches extended Saxton’s house. The massive south wing was probably added by the Lintalls around 1829, and the final gentrification was carried out by Major-General Bailie in the 1890s.

The garden is not easily datable – it could have been established by Saxton, or the next leaseholder, William Birch, or his son of the same name. In any event the Wilderness, perhaps created as an orchard after the principles set down by Lawson in 1618, is a significant element of the design. However, it is possible that the moat was already there and it began as a copy of one of the late medieval pleasure gardens such as at Kenilworth or Lyveden.

© AAAHS and contributors 2021

[1] William Lawson (1618) A New Orchard and Garden, or, The best way for planting, grafting, and to make any ground good for a rich Orchard: Particularly in the North and generally for the whole kingdome of England’. Lawson thought that a moat was the best fence for an orchard as it ‘will afford you fish, fence and moysture to your trees, and pleasure also, if they be so great and deepe that you may have Swans, & other water birds, good for devouring of vermine, and a boat for many good uses’.

[2] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/berks/vol4/pp333-334 also pp.369-379.

[3] Gelling, Margaret ‘The Hill of Abingdon’ Oxoniensia vol. 22, (1957) pp. 54-62; Kelly, S E (2000) Charters of Abingdon Abbey vol.2 (Oxford, 2000).

[4] https://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/berks/vol4/pp369-379

[5] The first Richard was probably the Richard who was mayor in 1564 (Richard Smyth (or Smith) | Abingdon-on-Thames)

[6] https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/25907

[7] TNA PROB 11/151 He died in Shrewton Wiltshire in 1626, and owned a number of properties in addition to Caldecott.

[8] Will TNA PROB11/788/487. His wife, Frances, received an annuity. He had an interest in an East Indiaman, the Prince Edward, launched in1746 (British Merchant east indiaman ‘Prince Edward’ (1746) (threedecks.org)

[9] Cox, Mieneke Abingdon, An 18th Century Country Town (Abingdon, 1999) p.105 quoting Jackson’s Oxford Journal 6 April 1754. See also https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/4780; Will, TNA PROB 11/811/374, dated 1752, where he is described as ‘of Caldecott’. Wm Birch witnessed his Will.

[10] Cox, An 18th Century County Town, p.155. For her correspondence see Clark, Gillian (ed.) Correspondence of the Foundling Hospital Inspectors in Berkshire, 1757-68. Berkshire Record Society volume I. (Reading, 1994), BRS_Volume1_Text_pp1-124.pdf (berkshirerecordsociety.org.uk) pp. 116-117. See also TNA PROB 11/1340/18.

[11] TNA PROB 11/1340/18

[12] Berkshire Record Office (BRO) D/EX458/3 Sarah was probably one of the Birch trustees.

[13] Cox, An 18th Century County Town, p. 147 quoting Jackson’s Oxford Journal 29 April 1780; p.210 for St Helen’s churchwardens’ accounts for 1778 and burials 1787.

[14] Angus Library ref. STE 5/12/v. All these letters have been transcribed, with a commentary, and are on the Univ. of Southern Georgia website (https://sites.google.com/a/georgiasouthern.edu/nonconformist-women-writers-1650-1850/steele-mary/mary-steele-s-correspondence/mary-steele-s-correspondence-with-her-sisters#_edn90

[15] https://sites.google.com/a/georgiasouthern.edu/nonconformist-women-writers-1650-1850/steele-mary

[16] Jane Austen — Letters — Brabourne Edition — Letters to Cassandra, 1796 (pemberley.com)

[17] For Holwell see https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/13622

[18] TNA PROB-11-1512-134 where he is ‘of Goosey and of the parish of St Helen’s in Abingdon’ (1810)

[19] ODNB https://doi.org/10.1093/ref:odnb/24759

[20] https://newspaperarchive.com/london-standard-may-04-1829-p-1/

[21] Their later divorce is detailed in Edward Loveden Loveden | Abingdon-on-Thames; For Mrs Lintall, Jackson’s Oxford Journal 24 June 1820

[22] Gentleman’s Magazine. See also his Will PROB 11/1942/424 at TNA. In some sources he is Lintell.

[23] TNA PROB 11/1942/424.

[24] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 17 April 1841; Aldingham Hall list entry number 1088640.

[25] TNA PROB 11/2093/355.

[26] Unpublished ms diary of R J Spiers (OAHS); for Spiers see http://www.stsepulchres.org.uk/burials/spiers_richard.html

[27] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 8 April 1854.

[28] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 4 November 1854.

[29] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 9 June 1855.

[30] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 7 February 1857.

[31] Abingdon Railway Co minutes are at TNA ref RAIL 5

[32] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 25 July 1857.

[33] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 29 May 1858.

[34] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 18 November 1871.

[35] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 2 August 1873.

[36] Jackson’s Oxford Journal 9 January 1875.

[37] https://www.ancestrylibraryedition.co.uk/search/collections/1904

[38] Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 17 January 1880.

[39] Index of Wills (https://www.ancestrylibraryedition.co.uk/search/collections/1904)

[40] Jackson’s Oxford Journal, July 8 1882.

[41] Jackson’s Oxford Journal, 1 March 1884.

[42] Bailie, George Alexander, A History and Genealogy of the Family of Bailie of North of Ireland (Augusta, Ga. 1902).

[43] The London Gazette, 7 July 1885 p.3118

[44] Also of this family are the Millers of Shotover Park. Sir John Miller (d.2006) had a huge stuffed Russian bear in the entrance hall there.

[45] 1891 census Sutton Wick. RG.12, piece 981, folio 98, page 11.

[46] The height of the flood water is marked on a plaque on the left-hand pier of the entrance to St Helen’s churchyard from the Wharf.

[47] http://www.greatwarbritishofficers.com/index_htm_files/BAILIE_T_M_D_Research.pdf; Gray, Jane and Rayner, David, personal communication: The History of Grestun (Caldecott) Manor Unpublished draft (2006).

[48] Thomas, Judy and Drury, Elizabeth, More of Abingdon Past and Present, (Stroud, 2008) p.51. From the sale catalogue of 1935.

[49] Country Life, 6 July 1935.

[50] Berkshire Record Office ref. D/EX458/3 BRO: New Landscapes (berkshireenclosure.org.uk)